Up Close: Mariah Fredericks

A Heroine of Great Importance

Some fans of Downton Abbey are obsessed over Lady Mary’s marriage and romances, the travails of her sister or the quips of Dowager Cora. Not writer Mariah Fredericks. “I watched Downton solely for the downstairs stories,” she says. “I thought the most compelling, moving couple in the show was Carson and Hughes; forget Mary and Matthew or Mary and her interchangeable brunettes.”

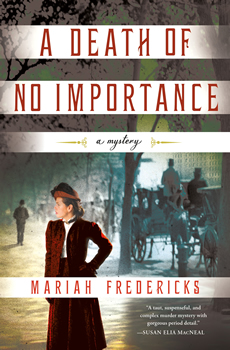

So when Fredericks decided it was time to write her own historical mystery, she created a heroine who was very much downstairs. The result is a compelling story of a maid in 1910 New York City, employed by a family with riches but not a lot of culture. A murder in the Gilded Age circle reverberates in ways no one could have imagined. Publishers Weekly gave the book a starred review, saying, “The novel’s voice, plotting, pace, characterization, and historical background are all expertly crafted…”

We asked Fredericks more about her novel A DEATH OF NO IMPORTANCE.

You’ve written some wonderful YA novels. What led you to write an adult book?

Thank you. I ran out of adolescent angst. After eight books, I had mined every last horror story of my teen years. With the exception of my one summer at sleep-away camp. One day, I may have the courage to put that experience on paper.

I also love history and that can be a hard sell in young adult novels. They’ll let you kill any number of people, but if you set the murders in the past as opposed to a fabulous movie-ready dystopia, it’s problematic. So when I realized I wanted to write a mystery from a servant’s point of view and that the context was going to be certain aspects of American history, I knew it had to be an adult novel.

Your YA novels were not set in historical period, so what made you decide to not only write an adult novel but also set it in another time?

I didn’t really make that call. My narrator, Jane, did. A DEATH OF NO IMPORTANCE started about 10 years ago when the first line—I will tell it—popped into my head. And the speaker’s language felt formal, old fashioned. This was not a modern teenager’s voice. I love reading historical fiction. I got hooked on Jean Plaidy and Rosemary Hawley Jarman as a kid. And I’ve always been fascinated by what servants see and hear. I’m absolutely team Downstairs. To tell this woman’s story, I needed a time when people had servants, but one that would be modern enough so I wouldn’t have to conjure a world that was completely gone. You can still find Gilded Age New York in today’s city, in architecture, public spaces, even some bars and restaurants.

What was the particular inspiration for this mystery and why did you pick the year 1910?

I wanted a past New York, but I wanted a time of class tension, even violence. Gilded Age lends itself to that. But I wanted a glimmer of modernity, advancing technology, the rumbles of World War I—not just Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence. The Triangle Factory Fire has always haunted me and I knew I wanted the book to end with that event. That was March 1911, so I just backdated to 1910 for the main events of the story.

Why a servant for your main character and not one of the middle class or upper class members of New York society?

At one point in the book, the tabloid reporter says, “My theory is the people who cook the food and clean the clothes see and hear a lot more than the people they work for.” I was a very quiet kid, a listener. And as a result, I heard a lot of gossip. People trusted me. So I was interested in working with that dynamic.

Most of us aren’t exceptional; most of us follow—roughly—a path that’s acceptable to our family, our class. Jane is very intelligent and she does end up doing things even she would not have expected of herself. But I didn’t want her to be an outlier, a rebel. Her friend Anna has that covered! Upper class people have more freedom to break rules. She could have been middle class, but I specifically wanted someone without a lot of power, someone no one would notice, as my sleuth. It was interesting to learn in the research process that servants were not to knock on doors; their presence was supposed to be so unobtrusive, so they could simply glide in and out without disturbing anyone.

What do you think of the way servants are depicted in turn of the century and early 20th century TV series and movies?

The servants are always more interesting to me than the masters. Some people want to hear they’re the reincarnation of Cleopatra or Catherine the Great; I strongly suspect if we have lived before, I was the servant who said no thank you to the asp and crept out the back way. There’s something in the tension between trying to create a perfect world for someone else as you struggle with cold rooms, sore feet, tired eyes, loneliness—and in many cases, outright abuse—that’s intriguing. Let’s face it, all those dramatic depictions—including mine—are fairly idealized. We’re showing servants of the richest families. In both Downton and my book, the lady’s maid enjoys a level of trust and devotion from her employer that was probably atypical. Lady’s maids were high in the hierarchy of staff—but still, they’re staff!

Did you ever consider writing a main character who is a police officer or detective rather than an “ordinary” person, and how hard was it to get her into places she would need to go to investigate the crime?

I never considered having a professional detective as my main character for two reasons. One, I have zero knowledge of police procedure—not that there was a lot of actual procedure in the 1910s. Two, I approached the solving of the mystery from the point of view that many of us do when we’re following crime in the news. We want to know who is guilty, we want to know why they did it, and we sometimes think about what it says about us as a society that such a crime was committed. What did the Preppy Murder tell us about teenagers in the 80s? What did OJ tell us about race and celebrity? I wanted Jane to have a similar perspective of the crime that most readers would.

How do you keep the suspense high during a historical novel with multiple characters?

Well, you cross your fingers and hope you did. What I tried to do is create a world where people have enormous power over others and trust is fragile. In the book, almost everyone’s future is tied to the Newsome family in one way or another. Charlotte Benchley and Beatrice Tyler’s social and financial future is tied to the victim, Norrie Newsome. Anna, Jane’s best friend who is a labor organizer, sees them as exploiters and murderers of working people. The reporter Michael Behan sees the story of the murder as a way to pay his bills. There was no social safety net at this time. You worked hard or married or inherited. So I tried to give as many characters as possible a strong stake in the murdered man’s life and death and to create other smaller betrayals along the way.

What’s your next book?

More Jane! Death of a New American comes out next April. It’s 1912, an election year. Teddy Roosevelt is taunting Taft. The Titanic has sunk, suffragettes are on the march. Anti-immigrant, especially anti-Italian sentiment, is high. And there’s a wedding. And a murder. I loved writing it. I hope people enjoy it.

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018