International Thrills: Ramón Díaz Eterovic

The Darkness That Never Leaves

By Layton Green

By Layton Green

World-weary private investigators, talking cats, political intrigue, and a murder mystery that reaches into the troubled past of South America: What’s not to like? This month’s globe-trotting literary adventures take us to Chile, a country that stretches almost the length of South America and is home to some of the world’s best hiking, wine, and ski trails. Though known for beautiful nature and the warmth of its people, it carries the dark stain of the Pinochet regime, a brutal military dictatorship in power from 1973 to 1990.

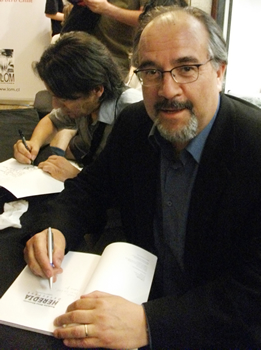

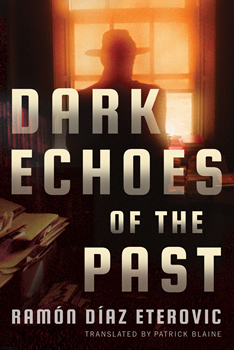

Our interview subject, Ramón Díaz Eterovic, explores the lingering impact of the regime in DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST, the first of his best-selling novels featuring private investigator Heredia to be translated into English. Ramón is one of Chile’s most beloved authors, and delivers that rare breed of crime novel: a page-turning mystery that serves as a medium for an incisive examination of society and the human condition.

Ramón has also published novels, books of short stories, children’s books, and poetry. His work has won numerous awards, been translated into a dozen languages, and has appeared on Chilean television.

This interview was translated by Patrick Blaine.

Thanks for taking the time to chat, Ramón. We’re thrilled to have you. Can you tell us a bit more about your background? Where are you from and how did you come to be a writer?

I was born in the city of Punta Arenas, on the shores of the Strait of Magellan in Chilean Patagonia. It’s a snowy, windy place that was settled at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century by immigrants from a number of countries. My maternal grandfather was one of them, and came from Croatia. In this city I lived out my childhood and teen years. When I was 17, I traveled to Santiago, the capital of Chile, to study political and administrative science at the University of Chile. I currently split my time between Santiago and Villarica, in the south of Chile, a place characterized by beautiful lakes and volcanoes.

Years ago, during one of the rough winters that punish Punta Arenas, I discovered that the windows of my house were covered with frost that I used to write the first letters I had learned in school. Through those letters I could see my backyard, the animals that my mother tended, the gray or blue sky (depending on the time of year), the snow, and the neighbors on their way to work. That is to say that through those letters drawn on glass I could see a fragment of life. Since those childhood years, and my first readings, and surely without knowing it until much later, this innocent attraction gave birth to my fascination with portraying my world or building others with words.

Like almost any writer, I began as a passionate reader. At the age of 10 or 12 I read comics, and soon moved on to authors like Jack London, Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, and many others. There were also two Chilean authors that are still among my favorites, Manuel Rojas and Francisco Coloane. After that came the time of the Latin American Boom authors like Juan Carlos Onetti and Julio Cortázar. At 14 or 15 I wrote my first stories. I didn’t have any teachers or older writers to show me the way, and so I learned to write with the most effective resources that a writer has for creating work: reading all the books I could get my hands on and writing as much as I possibly could. As a university student I won a handful of prizes and also met aspiring writers like myself. Both things were important in my development as a writer. I published my first book in 1980, and since then I haven’t stopped writing. I have published 30 books, not all of which were novels, and some have been published in a dozen languages apart from Spanish.

I really loved DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST. The novel concerns a private detective’s search for some of the torturers responsible for human rights atrocities during the Pinochet regime. While it sounds heavy like a heavy topic, and it is, I think the genius of the novel is how you subtly weave the political themes into a fast-paced mystery that has plenty of heart, soul, and even laughs. If you don’t mind talking about it, how did this dark period in Chile’s history affect you personally?

That was a period in the history of my country that affected me in many ways. I was 17 years old at the time of the military coup, and I watched as classmates from my high school were detained, beaten, and sent to prison camps, such as the infamous Dawson Island, where many people were tortured. I lived the next 17 years under the dictatorial regime, and I was 34 when I voted in a presidential election for the first time. Many of the subjects that I wanted to study in the university were banned from academic programs. Writers that I wanted to meet were detained or forced into exile. In 1976 I was kidnapped by the dictatorship’s secret police, and in 1985 I was fired from my job for being part of a political movement that fought against the military regime. In general, I would say that, like many Chileans, I had to learn to live with fear while gathering the energy and hope to participate in resistance activities. Because of all of this, and some other reasons that I won’t get into, that time has been and is important to my writing.

How repressive was the regime to writers and the arts? When did the first novels about the period begin to surface, and are there any in particular you would recommend?

Many of the authors from the generations before mine were forced into exile or had to remain silent if they stayed. Of those that remained, some were sent to prison camps, such as Chacabuco in the north of the country. The rest of us had to learn to live with fear, censorship, the shuttering of publishers, and the permanent possibility of being detained for texts we read in public or that we began to publish, almost clandestinely, in order get our work out. Many books that interested us were banned, and we had to read them in secret. Among others, I remember I Confess That I have Lived by Pablo Neruda, and The Open Veins of Latin America by Eduardo Galeano. With respect to Neruda, I can add that there is a current investigation into the possibility that he had been assassinated through the injection of a virus while he was being treated in the clinic where he would ultimately die. To pull all of this together, it was a difficult time to survive in and to write, but we did so with the idea of resisting through literature and creating the conditions for democratic recovery.

Of the first memoirs written about this time, and all were published outside of Chile, I remember the book Tejas Verdes (Green Roof Tiles) by Hernán Valdés; the novels En ese lugar sagrado (In That Sacred Place), by Poli Delano; Un día con su excelencia (A Day With His Excellence) by Fernando Jerez; Viudas (Widows: A Novel) by Ariel Dorfman; and La casa de los espíritus (The House of Spirits) by Isabel Allende, among others.

How is the political climate in Chile today?

The return to democracy occurred in 1990, and since then we have lived in a climate in which we can express ourselves without fear. The political parties that were prohibited are back, along with some new ones. Even though there are still many legacies of the dictatorship, above all in the realm of economics, education, and social security, there is no doubt that we are living in an epoch different from that of the government of Pinochet and his henchmen. Writers can publish and share our works without problems, with the exception of the limitations caused by a reduced number of publishers and the lack of variety in media. We are missing things that are needed for a fuller democracy, but there is no questioning that the situation is better than what we lived through in the past. Another thing that we need are policies that help to mitigate the high level of economic inequality in Chile.

Getting back to DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST, why did you decide to write a detective series?

My work as a detective novelist was born out of my fascination with a genre whose stories I always found attractive because of the way the characters fed my desires for adventure and justice. I was also looking for a form of expression that would allow me to convey the feeling of a culture under surveillance, specifically Chilean society as it was some years ago.

My novel La ciudad está triste (The City Weeps), written in 1985 and published two years later, marked the birth of Heredia, the detective that has accompanied me through 16 novels, a graphic novel, and a television series. It was also the beginning of a project that reflected a double marginalization. First, writing out of the codes of a literary form that is little explored in Chilean literature, and second, tackling issues that at the moment were difficult to speak aloud: political repression, the reality of the detained and disappeared, and the corruption of public power. These themes gave way to others with time, such as the prevalent racism in Chilean society, the abandonment of the elderly, arms trafficking, narcotrafficking, and ecological crimes. Looking at the totality of the Heredia novels, I feel as if I have traced the path of Chilean history over the last four decades. In all of them there is an evident counterpoint between literature and history, between reality and fiction. My intention has simply been to write from the codes of a literary form that I am passionate about, and that my words provoke readers to be more attentive, less complacent with the past, and the time we now live in.

How did private investigator Heredia, your main character, evolve?

When I began to think about the Heredia novels as a longer-term project, I decided that he would be a character that aged, and that he wouldn’t be a character that remained static in time. On one hand this seemed more realistic, and on the other it allowed me to turn the Heredia series into a sort of chronicle of Chilean society. For the latter it was necessary for Heredia to function as a witness, and to live through the events that occurred in different periods of Chilean social life. The aging of the main character implies a creative challenge in showing a character who changes, and at a certain point doesn’t have the swiftness that he did in the first novels, and begins to feel the afflictions of age. He experiences both psychological and physical changes. The only thing that does not change is the ethic and will for arriving at the truth that has identified Heredia since his birth.

Just a wild guess: do you own a cat? I confess I’ve never read a series where the detective talks to his feline companion about life, love, and catching the bad guys. I loved it (and I’m not even a cat person).

The main—and at times only—company that Heredia has is a white cat named Simenon, in homage to the creator of Inspector Maigret. Heredia carries on dialogues with his cat that serve to reflect upon existential uneasiness or about the details of crimes that he investigates. Also, the cat’s speech serves as a critical counterpoint for Heredia’s actions or his doubts, which are sometimes significant. In these conversations, Heredia often comes to realizations that allow him to zero in on clues or his intuition.

In the first novels in which Simenon appears, the cat doesn’t talk, or better stated, Heredia doesn’t imagine that he can talk to his cat, but soon the dialogues increase in frequency and constitute a significant element in the development of the novels. It is also an ingredient that some readers are especially attached to, both because of the humor and irony that the conversations employee and because they also contain a number of reflections that fill out Heredia’s psychological profile. In the end, the dialogues that Heredia imagines himself having with his own cat are dialogues with his own consciousness. He is talking to himself, not with the cat.

The book is full of lovely, pithy nuggets of wisdom. Do these roll off the pen, or is it something you have to work at?

They are ideas, reflections, and observations that come to me naturally as part of the writing process and the themes that I’m touching on in a given novel. I’m interested in telling attractive stories, but at the same time I want them to have elements that cause readers to reflect upon the beauty and misery of the world we live in.

I took a trip to Santiago some years ago, and it was great to revisit the city in the novel. How has the city changed during your lifetime?

Santiago has changed a lot. I arrived in 1974, and since then I have seen it grow and modernize permanently. It is one of the most modern cities in Latin America. The relationship that Heredia establishes with the city, and especially with one of the oldest and most traditional neighborhoods, allows him to perform a sort of urban registry that names places that are being destroyed. These changes aren’t part of the normal architectural changes of a city, but are instead a product of changes in lifestyle and the erasure of the country’s memory. I understand the possibility of preserving some traces of the past city as an exercise in urban memory and I effectively use Santiago as a character in the stories that I write.

Who are some of your favorite crime novelists, both at home and abroad?

Some Chilean authors that I enjoy are Luis Sepúlveda, Juan Ignacio Colil, Gonzalo Hernández, Bartolomé Leal, and Antonio Rojas Gómez. The list could be much longer, because among other reasons, the last years have seen an uptick in the number of authors writing within the codes of crime fiction. This makes for a much different scene than when I published my first Heredia novel. At that time the detective genre wasn’t very esteemed by the publishing world or critics. Today that situation has changed. Crime fiction has much more space in publishing houses and critical spaces. It is also studied in the universities, and is considered a literary form that has contributed to reflecting upon the relationship between power and criminality in Chilean society.

As for authors from other countries, I can mention writers like the Mexican Elmer Mendoza, the Argentines Juan Sasturaín and Mempo Giardinelli, and the Bolivian Gonzalo Lema. Leonardo Padura, a Cuban, and the Rubem Fonseca from Brazil have also been important. From Spain, Juan Madrid, Manuel Vásquez Montalbán, Andreu Martín, and Alexis Ravelo are notable. Ultimately, the list could always be longer. I’m also interested in authors like Henning Mankell, Ian Rankin, Arnaldur Indridason, and Pierre Lemaitre from France, and Michael Connelly. Finally, among the classics, Georges Simenon, Jim Thompson, Horace MacCoy, and Ross MacDonald are indispensable.

I’m curious about literary tastes in Chile — what does the public like to read? How do thrillers and mysteries fare?

In general people in Chile read a lot of Spanish and Latin American authors. U.S. writers like Philip Roth, Paul Auster, and Charles Bukowski are popular. People read a lot of scholarly books about the political and historical events in Chile. They also read a lot of poetry, which is rich and varied in Chile. Self-help books are popular with many readers. As it concerns crime fiction, I would say that there is a larger and more enthusiastic audience than in the past; however, we still lack better distribution of foreign authors, and in many cases people only read authors that have been translated into Spanish in Spain.

What advice would you pass on to budding novelists?

I always say the following to the students that participate in the workshops that I lead: the only valid method is to read and write incessantly. By reading we learn how other authors resolve their narrative situations; by writing we improve in the trade and in the ability to create our own stories. To this we have to add the factor of time that is indispensable to realize our creations. Writing a novel is a long distance race, and to arrive well at the finish line requires preparation and willpower.

What are you reading right now?

For the last couple of weeks I’ve been reading two Chinese authors. The novels Big Breasted and Wide Ships by Mo Yan, and One Word is Worth Ten Thousand Words by Liu Zhenyun. I’ve also been reading a biography of Jim Thompson, Savage Art, and a really entertaining book on the wide world of the crime novel, “Sangre en los estantes” (Blood on the Shelves), by Paco Camarasa.

What can we look forward to next?

In the U.S., DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST will be released on December 1st, 2017. We’re in conversations with my publisher to translate and publish the novel Ángeles y solitarios (Angels and Loners) in the near future. At present I’m working on novel number 17 of the Heredia detective series, and I’m also preparing a re-edited collection of my short stories to be published in 2018 by LOM, my publisher in Chile. I’d also like to add that 2017 has been important for the distribution of my books outside of Chile. In the beginning of the year DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST (La oscura memoria de las armas) was published in Spain, and my novel La música de la soledad (The Music of Solitude) was published in France, where it was titled “Black Loneliness.” Finally, La oscura memoria de las armas (DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST) is about to come out in Venezuela.

STYLE NOTES from the TRANSLATOR

Where an English translation existed, that title is used and appears in italics. Original Spanish titles are included in Italics for all books mentioned by Ramón, with the exception of a paragraph where Neruda’s autobiography and Galeano’s The Open Veins of Latin America are discussed. The rationale for including Spanish titles is that some readers may want to find these books in the original, and most of them have not been translated into English. The original title of DARK ECHOES OF THE PAST is given in a number of instances out of respect for the author and his work. Title translations where a published translation does not exist appear in the normal font. All of these translated titles are mine.

- International Thrills: James Wolff - June 30, 2018

- International Thrills: Sara Blaedel - April 30, 2018

- International Thrills: Ramón Díaz Eterovic - November 30, 2017