Trend Report: Where is the Horror Novel Headed?

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

It’s impossible to overstate the impact of Stephen King on the realm of horror fiction.

Beginning with the seminal novel The Castle of Otranto in 1764, horror fiction has flourished, pouring from the pens of Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, and Bram Stoker. But in the 20th century, ever since Carrie was published in 1974, an immeasurable number of scribes have been inspired by Stephen King’s pet burial grounds, creatures in the mist, world-decimating plagues, haunted cars and hotels, twisted dimensions, and perhaps most relevant today, killer clowns.

Last month, Stephen King’s It dethroned The Exorcist to become the highest grossing horror movie of all time, bringing in more than $500 million—a rarity for any film, but history-making for the genre.

Twenty years from now, King’s influence will still be profound, but with Pennywise striking terror in every major movie theatre across North America, it’s hit a sweet spot of respect that is also fueled by nostalgia.

“Properties like Stranger Things and Andy Muschietti’s It adaptation don’t just channel our nostalgia for ’80s horror, they evoke the fear and pain of growing up, along with the power we find in friendship, empathy for others, and the growing sense of autonomy that comes with adolescence,” says April Snellings, an author who writes about horror for a living. “His popularity set off an explosion of horror literature in the ’80s, which led to a market glut.”

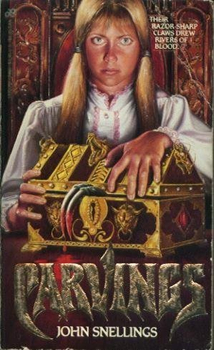

Snellings’ father, John, was one of those horror writers who rode the King boom for a brief while before the genre dipped. Thanks to the box office success of It, the genre may be going through a King-inspired resurgence.

“Interest in horror as in other genres is cyclical, and all this attention on Stephen King can only result in some trickledown to other authors and projects as everyone searches for the next It,” says Monica Kuebler, books editor of Rue Morgue Magazine. “Yes, the latest adaptations of his work, and the works of his progeny, are drowning out a lot of other horror titles in the mainstream media at the moment, but there are still plenty of releases rolling across my desk and making waves in genre circles, and getting optioned for television and film for that matter.”

Kuebler notes a trend toward ensemble casts, often featuring children and teens, as well as period pieces—but writers are also keenly on the lookout for new ways to deliver spine-tingling chills that can withstand the inevitable genre “bust.”

“I feel like we’re in a period of seeking right now,” says Kuebler. “Zombies have finally run their course, more or less, and the next big thing has yet to break. That said, history has shown that horror tends to thrive during periods of political and social unease and unrest, so we may just be on the cusp of another boom.”

Which may be why another trend of the genre appears to be zeroing in on some of the issues making headlines—there’s nothing like a good scare for finding society’s open wounds and picking at them until they bleed. Consider the large number of monster movies produced in the wake of World War II, when fears of the atom bomb and radiation gripped America.

“I love that horror is becoming more inclusive, with some writers even confronting the genre’s own demons,” says Snellings. “I love that Matt Ruff (Lovecraft Country) and Victor LaValle (The Ballad of Black Tom) are writing Lovecraftian fiction that takes Lovecraft to task for his racism rather than excusing it as a product of his time. Racism is the horror, and that’s powerful, relevant, and chilling.”

Snellings says if she could issue a challenge to the genre as it looks to the future, she’d push for horror that further taps into the pulse of humanity, covering issues such as misrepresentation, intolerance, and hate.

“I want a supremely scary haunted house story where the main character is African-American, or a slasher story where the ‘final girl’ is a woman in her fifties,” Snellings says. “I want cosmic horror with queer themes, or stories about witchcraft that aren’t rooted in Western culture and folklore. I want feminist horror and horror with a big, beating heart, like It and Stranger Things and the 2015 movie The Final Girls, which is fantastic and you should watch it immediately if you haven’t seen it.”

Something to aspire to for sure, but first the genre must be willing to truly enter the spotlight, climbing out from behind Stephen King’s shadow. In its quest for perseverance, horror has become sneakier, shrugging away from conventional definitions, and worming its way onto the shelves in areas other than the shrinking designated “horror” section. Horror, like romance, is subjective—your thriller, for instance, might be someone else’s worst nightmare.

“Jaws is a monster movie to me, even though I’m aware that sharks are actual things,” Snellings points out. “The Silence of the Lambs is horror to me, but not in the expected sense; I feel fear and dread for Clarice Starling and Catherine Martin, rather than of Buffalo Bill and Hannibal Lecter. And the line between horror and other genres is so malleable—a story about a woman being relentlessly pursued by an emotionless, preternaturally strong, unkillable male intent on murdering her could be Halloween, or it could be Terminator, which, incidentally, terrified me as a kid and has many of the hallmarks of a horror movie, though hardly anyone would call it one. In Psycho, the line doesn’t exist at all.”

This ever-moving line has not only created confusion among horror enthusiasts, it’s made some people—fans and creators alike—hesitant to define it, and thus, trickier for trends to be tracked. When asked to comment for this article, two industry representatives declined, saying that the market seemed to be shifting, or the genre was too complicated to categorize.

They’re not wrong.

Eric Rickstad, the bestselling author of The Silent Girls and the follow-up The Names of Dead Girls, would argue that his books contain elements of horror—the Gothic setting, the ever-present feeling of doom. And yet, you wouldn’t find his stories tucked in the horror section at any bookstore.

“If you’re up all night reading, and you’re filled with an intense unease, then that’s a horror,” he says. “But we could debate genre all day long and still not come up with a definition.”

Riley Sager’s Final Girls is another perfect example. No one is calling it a horror novel—Stephen King dubbed it a thriller in his glowing blurb—but it deals expressly with slasher movie tropes and one of modern horror’s most beloved archetypes, Snellings says.

“I know people who insist they don’t read horror, even though their shelves are full of Stephen King and Dean Koontz. The cycle is always the same: I tell people I write about horror for a living, they say, ‘Oh, I hate horror!’ and then they tell me how they can’t wait for the next season of Stranger Things or The Walking Dead.”

Clearly, the definition requires some fine tuning. In an informal survey among a handful of friends, few could cite more than five books they’d rank as true horror, and more than half named Stephen King, Edgar Allen Poe, Lovecraft, and Dean Koontz as horror authors.

As a genre, horror revolves around literal and abstract monsters, and a protagonist’s struggle for survival and fear of the unknown. Horror aims to scare an audience through “gross-out” or “creep-out” factors, or in some cases, a combination of both.

“I tend towards broader definitions, because I think some of the most interesting contemporary narratives occur in the places where the horror genre cross-pollinates with other genres,” says Kuebler. “And the more this occurs, the harder it is to fit stories into simply labelled boxes, which is a good thing. Good horror should push boundaries or cause us to look deep within ourselves at the scary and unseemly parts.”

That’s certainly what connoisseurs of the genre want, but the success of It and all this talk about horror trends doesn’t necessarily translate to a buffet of fresh work. Definitions aside, there is still a stigma attached to the genre, and for new writers or young adult authors, in particular, it’s a trickier market to crack.

Literary agent and founder of Emerald City Literary Agency Mandy Hubbard says of YA, “Horror feels perennial to me—it doesn’t really boom as a genre, but it doesn’t really bust, either. I think psychological or campy works better than straight up gore.”

With few exceptions—such as the Scream-inspired Someone In in Your House by Stephanie Perkins or the Merciless series by Danielle Vega—the horror elements in young adult literature are somewhat secondary to the protagonist’s psychological journey. Horror grounded in gore or murder often reads too commercial for YA imprints, relegating it to paperback status, Hubbard adds.

Not that there’s anything wrong with commercial—it’s certainly worked for King and a handful of other well-read horror authors, and all signs point to it making a comeback—at least for a little while.

But if there is an area where horror fiction is struggling at the moment, it’s in the world of smaller presses, Kuebler says, noting that many publishers have closed their door and/or filed for bankruptcy in the past couple of years.

That shouldn’t deter writers, though. Fewer markets may just mean that authors have to dig deeper for scary stories that don’t lean on classic tropes. And for those willing to pick up the gauntlet, Snellings has some advice.

“Bandwagonism—that’s definitely a word, right?—is a great way to kill a monster. If you want to rob a trope of its power to scare us, put it on every available screen and page,” she says. “Zombies will get scary again, but for now we’ve become so inured to them that we’re making rom-coms (Warm Bodies) and charming mysteries (iZombie) about them. I love both of those properties, but they’re good signs that we’ve tamed rotters for now and that it’s time for horror creators to look elsewhere.”

Even if that means keeping only one eye open on what Stephen King is doing.

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025

- Don’t Look Down by Matthew Becker - February 15, 2025

- The Wolf Tree by Laura McCluskey - February 14, 2025