Africa Scene: An interview with C.M. Elliott

Writing the Post-Colonial Crime Novel

Born in England, C.M. Elliott is the author of the Sibanda series, crime and wildlife adventure novels set in the African bush. She moved from Australia to Zimbabwe in 1977 and has lived in and around Hwange National Park for a number of years. Her first full length novel, Sibanda and the Rainbird, was published in 2013.

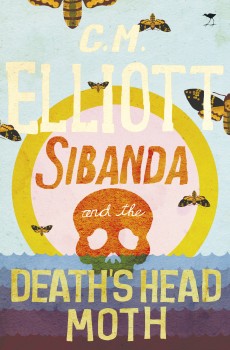

Congratulations on your second Detective Sibanda novel. Right from the start, I was intrigued by the title, SIBANDA AND THE DEATH’S HEAD MOTH, especially because of the creepy myths related to the death’s-head hawk moth with its skull-and-crossbones markings. How does the moth relate to the text here?

The death’s-head moth has stirred the imagination of the sensitive for centuries. The moth is said to have made its first appearance in Britain at the beheading of Charles I, a suitably spooky entrance. Bram Stoker stoked the spine chills by giving it a bit part in Dracula, and a starring role in The Silence of the Lambs cemented the insect into folk lore. In between, movies such as Un Chien Andalou, in which the surrealist Salvador Dali, had a hand, and the 1968 horror flick The Blood Beast Terror added grist to the growing legend.

The death’s-head moth has adapted into a clever and cunning hive burglar also known sometimes as the bee tiger. I chose it to feature in the title because not only does it have an evocative name but its ablity to disguise and deceive is an appropriate symbol for the murderer in the story–a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

We’ll get to the baddies later. First, how did Detective Inspector Sibanda evolve as a character?

Detective Inspector Sibanda started life in a short story, and I knew instantly that he was someone I wanted to spend more time with. He has so far been sparing with his personal details but I have learned this: He is tall, athletic, commanding, strikingly good looking, and saddled with a short fuse. He was brought up in a rural environment, went to a good boarding school, and soon after joining the police force was singled out for an overseas training scholarship in the UK–a blue-eyed boy, no less!

But something happened on his return to blot his copy book (he keeps this information particularly close to his chest), and he was posted to the sleepy outpost of Gubu in Matabeleland north on the boundary of a large national park. This hasn’t upset him at all, because along with his focus for solving crime comes a passion for wildlife (particularly elephants), birdlife and trees. The posting to Gubu allows him to indulge his love of the wilderness.

And like any good detective, the love of his life eludes him! This vulnerability makes him even more likeable, as does his wry reflection of his life in England.

Yes. The third passion in his life is Berry Barton, a beautiful, carefree girl with a tangle of blond hair. Oddly, he is unusually wrong-footed and insecure where she is concerned. His fears that he might find Berry dead “in some gruesome fashion” permeate the novel.

They met in England, became good friends, and spent most of their time together reminiscing about Zimbabwe. They made life tolerable for each other with their nostalgic talk of biltong, Mazoe orange and the first rains on dust–the missing sights and sounds of Africa. Both knew they were going home and that England was a temporary but necessary blip, so they sustained one another through their homesickness.

Tell us about SIBANDA AND THE RAINBIRD, the first in the series.

Detective Sibanda teams up with Thadeus Ncube, a rotund, digestively challenged, thrice married sergeant with a penchant for fizzy orange drinks and anything mechanical. This is just as well because the third in the crime fighting triumvirate is Miss Daisy, an ageing Land Rover rescued from the pound and given a new lease of life by Sergeant Ncube’s mechanical genius. She’s cantankerous in the extreme and given to inappropriately timed breakdowns; Sibanda is wary of her, Ncube admires her. Despite their differences and misunderstandings the three of them manage to solve a particularly hideous muthi murder, involving body parts and traditional medicine.

In SIBANDA AND THE DEATH’S HEAD MOTH, Sibanda must solve two murders: the killing of David Makhandla, bootlegger, and Tiffany Price, American nature conservationist and Rhino protector. David, in an original opening scene, is struck by lightning, but Sibanda’s astute observation ensures that his death is investigated as a homicide. The second victim, Tiffany, ends up on the wrong side of “Africa’s temper.” Are these deaths both consequences of Africa’s temper?

Yes. Africa can turn on you when you least expect it and has a sting in her tail worse than a scorpion–xenophobia, drought, poverty, corruption, in-fighting, inefficiency, and greed are some of her worst traits and all of them can cause her to hit out without warning. She doesn’t have the benefit of a measured temperament or the wisdom of maturity and sometimes I wish I could prescribe the occasional Valium, but on the whole Africa is well worth living with. I’m not ready for divorce, at least!

Throughout SIBANDA AND THE DEATH’S HEAD MOTH references are made to Zimbabwe’s problems – “toxic inflation.” the “borders as rotten as a vagrant’s socks.” In real life Zimbabwean police are up against corruption in the ranks, let alone political corruption. What are the challenges faced by your fictional police outfit in a faltering Zimbabwe?

All countries have their challenges, Zimbabwe more than most, but the population is resilient and of good cheer through the hardships when it would be easy to give in to despondency.

Gubu police station is short of everything, not only functional transport. Times are hard in the economically savaged Zimbabwe and a culture of make-do-and-mend prevails. Crimes are solved in the old fashioned way without the help of banks of computers and sophisticated software. Crime scene cameras, efficient forensics, and the paraphernalia of modern policing haven’t yet penetrated the rural wilds of Matabeleland, but crimes are solved, none the less, thanks to Sibanda’s instinct and genius. His legendary tracking and observation skills don’t go amiss either. Sergeant Ncube adds wisdom, social insight, and familiarity with village gossip to the mix.

How do you reconcile the dour state of affairs in Zimbabwe with your light-hearted approach? It seems as if you had plenty of fun writing these mysteries.

As to keeping the novels light and good humoured, it’s always best to moderate a bad mood with wit or a good laugh; shouting back rarely works… If my writing is humorous, it simply reflects the extraordinary people who laugh and joke their way through adversity. I didn’t plan a comical series but the characters seemed more than up for it so I just followed their lead!

And so get back to your lively cast, we soon find out that Tiffany’s life was complex with fraught inter-personal relationships. We meet her arch-rival in the love stakes, Amanda Carlisle whose “well-educated voice sends shivers down the spine of an English Duchess, and her fathomless brown eyes scare the cucumber out of a thinly cut sandwich.” (I do love your turn of phrase!) Another fascinating pair is Bigboy and his Chinese wife, Li. Do you have any favourites?

Of all the aspects of novel writing, I enjoy creating characters the most. From the cast comes the psychology, hopefully subtle and satisfying. Sometimes the characters drive the plot all on their own and I start to wonder what part I’m playing in the creativity process. I’m not sure I can choose a favourite. I could tell you who I like the least but that might give the game away…

One of the antagonists, Andries Nyathi, is a fascinating study of a poacher with whom one actually feels a little sympathy. On one hand his killing of elephant and other creatures is abhorrent, on the other he lives off the land and only kills from necessity. We don’t generally have sympathy for poachers, so this is an interesting character development. Can you comment on this?

I hadn’t thought of Andries, the poacher, as an antagonist but you’ve hit the nail on the head. He is the closest character to Sibanda and in some ways his alter ego and a worthy adversary. It is easy to become emotional about poaching. For some, it is life or death stuff, the difference between feeding your children or seeing them go hungry. For wealthier, often foreign, others, wildlife is sacrosanct and a measure of civilization, and they believe its continued survival warrants any amount of suffering.

Poaching and trophy hunting are both highly sensitive issues, viz the recent demise of Cecil the Lion. Cecil’s death has raised millions in a few weeks for the preservation of lions. On a dusty road, a young lad fills in potholes hoping to earn a few cents from passing motorists. His mouth and nose are being eaten away by leprosy, he will never gain Cecil’s viral fund-raising potential; he doesn’t have the same appeal. Where do our priorities lie?

Indeed. Yet as the plot thickens, we learn that the poaching is directly linked to the Chinese market for Rhino horn and elephant tusk. Surely this is indefensible?

The commercial poaching of tusks and horn is certainly indefensible. Guilt lies firmly with the end users and their ridiculous beliefs in the medicinal properties of exotic bone and hair. This is the 21st century, no one grown up and sane believes in the tooth fairy.

Rhinos are already probably doomed, their survival rests on test tube reproduction and breeding in foreign locations. Elephants still have a fair chance if managed well and protected from mass poisonings and dire droughts.

From muti murder to poaching, Sibanda has certainly faced challenges. In general terms, how would you describe this genre of the African mystery, the post-colonial crime novel, which capitalizes on humour?

“Crime in post-independence, self-governing, rural Africa” is long-winded. I’ve been trying to think of a clever epithet that isn’t dated or pejorative and it’s tricky. “Murder most African.” “Safari Sleuth.” The crimes are unique, and as one critic pointed out, not the sort of crimes faced by Inspector Morse!

Indeed! Zimbabwean village life is rather different than that of the fictional county of Midsomer. How do your international readers respond to your particular African charm?

My international readers seem to love it. All the wildlife anecdotes woven through with clues and adventure is what they comment on, that, and the characters of course! I’m not sure if they expect the safari element, but they do enjoy it.

When can we expect the new Sibanda novel?

I am currently working on the third in the Series, SIBANDA AND THE BLACK SPARROWHAWK. Sibanda is on the trail of a serial killer with Ncube and Miss Daisy by his side. It’s a tough case with multiple bodies and plenty of wildlife encounters.

*****

Joanne Hichens is an author, editor, blogger, and a teacher of creative writing. She is currently taking a break from teaching to complete a PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS). She is the author of DIVINE JUSTICE, a Rae Valentine thriller, which will be followed by SWEET PARADISE to be published in 2015. She has edited several collections of short stories, including the BED BOOK OF SHORT STORIES – a collection of writing by African women, and BAD COMPANY – a collection of south African crime-thriller fiction. She is curator of the SHORT SHARPS STORIES AWARDS, which is an initiative backed by the National Arts Festival to encourage the writing of South African fiction. The inaugural collection, BLOODY SATISFIED, a crime-fiction collection, was published 2013, followed by ADULTS ONLY – stories of love, lust, sex and sensuality, in 2014. INCREDIBLE JOURNEY will be published 2015. Joanne believes in promoting South African fiction in order to entrench a reading and writing culture.

Joanne Hichens is an author, editor, blogger, and a teacher of creative writing. She is currently taking a break from teaching to complete a PhD at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS). She is the author of DIVINE JUSTICE, a Rae Valentine thriller, which will be followed by SWEET PARADISE to be published in 2015. She has edited several collections of short stories, including the BED BOOK OF SHORT STORIES – a collection of writing by African women, and BAD COMPANY – a collection of south African crime-thriller fiction. She is curator of the SHORT SHARPS STORIES AWARDS, which is an initiative backed by the National Arts Festival to encourage the writing of South African fiction. The inaugural collection, BLOODY SATISFIED, a crime-fiction collection, was published 2013, followed by ADULTS ONLY – stories of love, lust, sex and sensuality, in 2014. INCREDIBLE JOURNEY will be published 2015. Joanne believes in promoting South African fiction in order to entrench a reading and writing culture.

- AudioFile Spotlight: March Mystery and Suspense Audiobooks - March 17, 2025

- Africa Scene: Shadow City by Natalie Conyer - March 17, 2025

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025