Africa Scene: An Interview with Priscilla Holmes

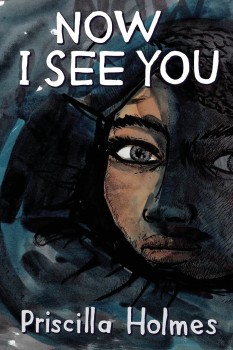

Priscilla Holmes is a Cape Town–based writer of many sorts of fiction, most recently a crime fiction novel. Set in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, NOW I SEE YOU is a modern-day thriller with dark undertones. It contains love and jealousy, human cruelty and sexual obsession, as well as humor and pathos. Part detective-story, part-elegy for a lost culture, it highlights the enormous changes that have happened, especially for young women in the years since the first democratic elections in South Africa. Thabisa Tswane (the feisty protagonist) is caught between two cultures. NOW I SEE YOU thrusts her into a powerful plot and some dark and dangerous situations.

Please tell us a little about yourself.

I’ve always been a writer. As a kid I wrote stories for all my friends and family, wrote plays at school satirizing the teachers (nearly got expelled!), and I’m a passionate reader. I worked most of my working life as a communications consultant in Australia, UK, and Hong Kong, and when I came to Johannesburg from Sydney to marry the man of my dreams (and yes, it has worked out!), I started my own training and communications business. We retired to Cape Town seven years ago and I started a writing group—The Write Girls—that has gone from strength to strength. We’ve collaborated on two novels that have been a great success. In 2004, I published a teenage novel The Children of Mer. And now, of course, I’m thrilled about the publication of NOW I SEE YOU.

NOW I SEE YOU has a deft, light touch. I think Alexander McCall Smith should make space for your fabulous Detective Inspector Thabisa Tswane! How do you feel about that?

Well, what a compliment! However, my book is a much darker, rougher version of his books. We are promoting it as a “thriller” but it really is so much more, with the descriptions of rural life, the violent crimes, and the constant fight for Thabisa between her past and present.

Is it fair to call it indigenous crime fiction?

Yes. South Africa is a country of such diverse cultures that it is fascinating to read about them and how they work. The rural culture of the Xhosa people is ancient and traditional and is how the indigenous people of Southern Africa lived hundreds of years ago. To find out that this life, these traditions and rituals still go on in the “lost” valleys and deeply rural parts of the country are an eye-opener for any visitor brave enough to seek it out.

Thabisa’s character is an immediate draw—the innocent “tribal” girl from the valley, who makes good, but ends up, as you mention, caught between two cultures. How did her character evolve?

I was told the true story of a “lost” valley by Joan Broster, a distinguished writer, of the Eastern Cape, whom I met by chance. We had a beach house in Kenton-on-Sea and I spent a lot of time in the area. Joan had once worked in a remote valley as a trader, and published several books on the beading and customs of the amaQaba people. She went on to tell me the story of a young Xhosa girl, from this very primitive valley, who was chosen to be educated. Joan knew this girl had also won a scholarship to a school in Grahamstown, but that’s where the trail ended. As soon as I heard the story of this unknown girl, I was determined to write the fictional version.

So Thabisa leaves the valley, her village, and her grandfather behind to get an education?

Yes, she’s the “lucky” girl who gets the scholarship. But it’s not all plain sailing. She incurs her grandfather’s fury when he concludes she’s turned her back on tradition. The Nguni Intile (Ancient Valley) is a deeply traditional place, ruled by the tribal chief. His word is law; he is obeyed by everyone and he punishes transgressors in a traditional, time-honored way. He only answers to the House of Tribal Leaders. Everything in the valley is dominated by worship of the ancestors.

Thabisa goes on to train as police, and joins the Violent Crimes Unit in Johannesburg, one of the toughest African cities. Would this have been unusual?

It certainly was unusual in those apartheid years for a woman to become a professional in any sphere. But I have interviewed several women police officers who did just that. It wasn’t easy for any of them. To go to university would have required some financial support; Thabisa didn’t have that from her estranged grandfather, so the police college was a compromise. Ambitious and highly intelligent, she went on to become a detective in an elite unit.

How did you learn about police procedure?

I approached mainly black women police officers in Port Alfred, East London, and Kenton, and interviewed many impressive women of around Thabisa’s age at the start of the book. They were full of fascinating, humorous, and quirky tales. I learned a great deal. Some of the officers I interviewed have done very well and now hold important posts as detectives, even Brigadiers.

In a way, NOW IS SEE YOU is a quest not just for Thabisa to solve an extraordinary crime, but a quest for her to affirm a balance between her rural past and current urban existence. Is this what she wants?

Yes, she wants success in her career. It means a great deal to her. She loves life in fast-paced Johannesburg. She’d like a good relationship, but hasn’t found the right guy yet. She’s cautious, so the two men who want her are going to have a hard time getting her!

She’s always got a nagging feeling in her heart about the valley she left behind. So much unfinished business there; all her roots; her childhood is full of valley customs. So many rural Africans do go back home, but Thabisa can’t, and at the back of her mind, it hurts that she left after the savage ritual punishment that was inflicted on her when she wouldn’t obey her grandfather and marry his choice of suitors.

The back story that refers to tradition is especially strong, and reads so authentically. I found the rituals and ancestry of Thabisa’s tribe fascinating. How did you research this?

Joan gave me a great deal of information and permission to quote from her book, Red Blanket Valley, published 1967. She shared many unique recollections of valley life, which I recorded and have used in NOW I SEE YOU. Sadly, Joan was very old and not in good health when we met, and she died before I had finished the book.

Apart from reading Joan’s books from cover to cover and every other book on the area I could get my hands on, Traders and Trading Stations of the Transkei by Michael Charles Thompson was especially helpful. I worked with Professor Andrew Spiegel at University of Cape Town, an anthropologist with special knowledge of Xhosa customs.

I’m sure you must have visited these places yourself, though?

Yes, I visited all the places mentioned. My husband, Jack, and I drove all over the area west of Mthatha, and north of Engcobo, visiting Queenstown, Elliot, Barkly East, Moshesh’s Ford, Rhodes, Naudesnek, and Maclear. Mthatha is the largest town in a coastal area, and used to be known as the Republic of the Transkei. The area was reintegrated as part of South Africa in 1994, as the Eastern Cape Province.

The scenery was dazzling, and we saw many small villages in deep valleys. We visited some on foot and were greeted with courtesy.

How did you discover “the way of the beads”?

Africa is known for beautiful beadwork, but this was different. I saw beautiful beadwork, less commercial from the normal beadwork we see in the shops—it was much more delicate and artistic. I decided to incorporate it in my story. I have certainly exaggerated the story of the beadwork for fictional purposes, although in some of the villages I observed that beadwork was used to record events.

A prodigious amount of research went into over fifty notebooks and dozens of recordings of interviews. That’s why it took me seven years to write the book.

Getting back to Thabisa’s love interests, do I detect here shades of Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plumb “torn between two lovers”?

I’m a fan of Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum. I wanted Thabisa to be more like Stephanie, with her quirky sense of humor and her two suitors. I guess that crept in with the gorgeous Zak Khumalo and Tom Winter the Aussie doctor—typical good boy versus bad boy stuff. Every woman who reads this book will identify with that dilemma.

Let’s touch on your bank-robbing criminals—the pair that Thabisa ultimately must track. Julia is the perfect foil for her captor, Sue. They are both sweet and rather vicious. Tell us more about them, with reference to the Stockholm Syndrome and the lesbian affair.

The baddies really took me over. Sue is the real baddie. Julia is the tragic wife of the revolting Magnus. No wonder Julia fell for the obsessive, stimulating, adventurous, yet vulnerable Sue. Here was an opportunity for a crushed woman to come to life, but I truly hadn’t planned the lesbian connection. The characters made me do it! I wanted two out-of-control white women to be a sort of a Thelma and Louise duo. I tried to make these criminals as realistic as possible, and yes it was my intention to juxtapose the more serious parts with humor.

Why did you decide to tweak out a more political strand? A sub-theme if you will, a story of three men betrayed by “inyoka,” which means snake in isiXhosa.

I really didn’t intend to bring apartheid into it as there have been so many books written about it already. But it’s like a jigsaw puzzle and the pieces just fell into place for me.

The interweaving of all these various threads is seamless. Was it a challenge to write from various points of view?

Not at all. I loved it. I’ve always enjoyed books that do this, give you different viewpoints about the same happenings. I loved all my characters and allowed them to evolve, their voices haunting me every day, and night. I’m sure any author would relate to that.

And of course, I have to ask what was it like writing from the point of view of a hip black female cop?

Well, I suppose that was the hardest part of writing the book. I had to continually remind myself that Thabisa had been brought up and educated, from an early age, as a white girl. Initially, for the first year of her schooling, she lodged with a family in Grahamstown, where she learned about living with a family group who were so very different from her own people in the valley. She learned the language and jargon of other young people, white people. The family where she was housed had three sons, so she had to communicate at their level to interact. She had to think like a white kid. Once she was at school she just fitted in. She was a smart kid and knew this was the way to get the best out of her schooling.

But the most powerful tool I had was my talks with the police officers who had walked the same route as Thabisa—what they had done, what they had experienced, and what their feelings were. They were genuine young women, all quite hip and fashion conscious, especially their hair, braids, and weaves. They all had issues about men dominating the profession and coming on to them. They were all cynical about relationships. They each had a great sense of humor about things, but not about their jobs.

I tried to get into Thabisa’s heart and soul. I lived with her for years.

An interesting departure for a crime novel is that the book jumps, at the end, from 2006 during which time the action is set, to 2012 (this disclosure involves no spoilers!). Why did you do this?

I wanted a resolution to Thabisa’s quest for self-discovery. That meant going forward to describe modern-day issues in South Africa, as well as how Thabisa resolved her rural versus urban life. I also wanted to end with the opportunity for a sequel. I am still haunted by Julia and what she became in the book, going from battered, depressed housewife to a dangerous criminal with a thirst for revenge. And in my sequel, she really comes for Thabisa—with all guns blazing. But that’s another story.

And I look forward to it! Thanks, Priscilla.

*****

Joanne Hichens is an author, editor, blogger at News24, and creative writing teacher at Rhodes University. Her novel DIVINE JUSTICE, featuring PI Rae Valentine, was named a Top Ten KillerThriller by the Sunday Times and a Top Ten LitNet Read for 2011.The sequel, SWEET PARADISE, will be out in 2014. BLOODY SATISFIED, an anthology of South African crime-thriller fiction, edited by Joanne,has just been released by Mercury.

Joanne Hichens is an author, editor, blogger at News24, and creative writing teacher at Rhodes University. Her novel DIVINE JUSTICE, featuring PI Rae Valentine, was named a Top Ten KillerThriller by the Sunday Times and a Top Ten LitNet Read for 2011.The sequel, SWEET PARADISE, will be out in 2014. BLOODY SATISFIED, an anthology of South African crime-thriller fiction, edited by Joanne,has just been released by Mercury.

To learn more about Joanne, please visit her website.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024