Special to the Big Thrill: Top Ten Firearms Mistakes in Fiction by Chris Grall

By Chris Grall

By Chris Grall

There is nothing I love more than a good story. I’ve been a voracious reader since the second grade, when I cut my teeth on just about every Hardy Boys book ever written. As I grew older and left Frank and Joe behind, my taste evolved to more complex fare. Growing up also meant a career, which for me happened to cultivate an expertise in firearms and tactics.

Put those two things together and you have an avid reader who recognizes weapon errors in fiction. If it were just firearms instructors who notice these mistakes, I wouldn’t worry too much about them. However, with between 270 to 310 million firearms in the United States* it’s a good bet that simple errors could distract many of your readers. Here are ten of the most common firearms mistakes that I’ve encountered, and some advice/tips on how to avoid them.

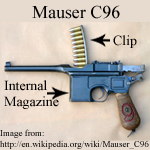

1. Clips and magazines (The most common mistake in fiction!)

While the term “clip” may seem interchangeable with the term “magazine,” they are completely different items.

While the term “clip” may seem interchangeable with the term “magazine,” they are completely different items.

Analogy: belt and suspenders… What’s the difference, they both hold up pants, right? Not necessarily.

A “clip” is a small metal device that bullets slide into. The clip is used to load a magazine that is internal to the weapon. The clip is discarded after the bullets have been loaded into the magazine. The M1 Garand is a WWII rifle that uses this loading system. Handguns mainly use a  detachable, or an ejecting, box “magazine.”

detachable, or an ejecting, box “magazine.”

All modern pistols use this system. In fact, the only pistol reloaded by a clip, that I’m aware of, is the Mauser C96. The C96 is one of the classic handguns German officers brandish in WWII movies—not exactly a common handgun on today’s streets. So, use “magazine” or the slang/lingo “mag,” when referring to loading and reloading handguns.

2. Guns clicking on empty

When a semi-automatic handgun is fired until its empty, the slide locks to the rear and the trigger is disengaged. The trigger can’t go “click.” Semi-automatic pistols go click only when the trigger is pulled, the slide is forward, and either the chamber is empty or there is a bad round in the chamber. A revolver can go click when it is empty because the cylinder will continue to rotate when the trigger is pulled. (Note: double action revolvers only.) In place of “clicking on empty,” describe how the slide has locked to the rear on an empty magazine.

3. Oops, it’s not loaded

Whether your character is using a shotgun or a pistol, if they rack the weapon before shooting another character, they have been menacing with an unloaded weapon. Racking the slide of a pistol or the pump of a shotgun can be very dramatic, but only in the right context. Ensure that your “expert” operator operates his/her firearm like an expert. See below: “Racking/Racking the slide.”

4. Putting guns on “safe”

There are many pistols out there that are not equipped with a safety that your character can manipulate. Revolvers generally don’t have a safety. There are also a number of semi-automatic pistols without this feature. In books, I often see characters putting their Glock pistols “on safe,” but Glocks don’t even have this feature: a dead giveaway to knowledgeable readers that you haven’t done your homework. Placing a Glock “on safe” is one of the biggest mistakes in fiction, and affects the way people in the know see you as a writer.

5. Cocking guns without hammers

As with item number 3, there are a number of pistols without hammers. These guns can’t be “cocked” by your character for that moment of drama. Make sure that you know the anatomy, features, and functions of the firearms in your story.

6. Running around with guns off safe

How an operator carries a firearm is dependent on two factors. First, what are the features of the weapon? Second, how was that operator trained? Pistols can be tricky. Single action semi-automatic pistols should be on safe until they are to be fired. Double action semi-automatics can be off safe when in double action mode, but should be de-cocked as soon as possible. Rifles should never be on “fire,” when not in an actual engagement. Highly trained operators don’t “go hot” and remove their rifle safeties going into a fight. This is because most rifles are ergonomically designed, placing the safety where it can easily be manipulated. It’s best not to mention the safety: readers will fill in the blanks based on their training, experience, or expectation.

7. Bullet effects

Much has been made of “stopping power” when referring to caliber, bullet weight, or type of bullet (such as hollow points). What stopping power actually refers to is the amount of damage done to a person. It is the damage that makes them “stop” what they are doing. Even though a bullet can deliver a massive amount of energy to a target, it doesn’t mean it can move that target. Bullets enter, and in many cases pass through the body—the classic movie trope of a bad guy flying backward after being shot by a high-caliber weapon does not happen in real life. The average 9mm round weighs in at a hefty quarter of an ounce. Stacked up against a 150-pound human, human mass wins. Even the venerable .00 buckshot round or 12-gauge shotgun slug will not throw back a shooting victim. When describing the effects of bullet strikes, stick to wound effects and internal ballistics: let Hollywood have victim acrobatics.

8. Caliber matches gun

You could say that your character is carrying a “Glock .40,” but there is no Glock model 40. Instead you are referring to the caliber of that particular model. It’s fine to use a weapon pronoun when writing, but be sure that you are not confusing the caliber with the model number.

9. Keep a good round count

If your character is involved in “The Shootout of the Armageddon,” make sure that they take time to reload every once in a while. A gun going empty at a critical time is a great drama builder, but it is dictated by the capacity of the weapon. If the weapon has a 15-round magazine you are permitted 16 shots (if your character is knowledgeable enough to load one in the chamber and also have a full magazine, a process called “topping off”; see the glossary, below). And if you do top off? Make sure the reader is shown that before the battle begins.

10. T.V. and movies for research

Visual media is choreographed for drama. Cops and bad guys hold their weapons so we can see their faces and the weapon. Or, the shot is framed to see the weapon in the foreground and another character in the background. This is visually stimulating and promotes an emotional response in the viewer. There are very few shows or movies that get modern tactics and techniques right.

The media that you’ve watched all your life influences how you describe your characters’ positions, actions, and how they handle their weapons. Make military and police contacts and ask if you can observe training. The way true professionals handle their weapons, move, and use cover is completely different in reality.

Final Words of Advice

1. Know your gun anatomy

Handle the guns your character uses. At a minimum, have a gun vendor explain how the weapon operates and what its features are. There are gun ranges where you can rent a gun and fire it. First hand experience is always best.

2. Talk to an expert

Ask a law enforcement officer how he or she carries and handle weapons. Techniques will vary greatly across different agencies, but this is a step up from a gun dealer of dubious experience.

3. Keep it simple

With such a wide variety of weapons and the techniques and tactics with which they are used, it’s easy to run afoul of somebody’s pet peeve. By keeping things simple you allow readers to fill in the blanks based on their own experiences. Remember, there is a fine line between “not enough” and “too much” detail.

4. Weapon pronouns

When using caliber as a pronoun you can drop the word “caliber” if you want. “He drew his .45 from the holster.” Caliber is understood if the period is before the number. However, never drop “mm” from the caliber pronoun. It is always 9mm. My guess is that this faux pas comes from gangster vernacular. Upstanding weapons operators always use millimeter when speaking of caliber. Nobody wants to sound like a gangsta. Well, unless they actually are a gansta.

Glossary

Racking/Racking the slide—Common terminology for chambering a round from a loaded magazine. A fully loaded magazine can be inserted into a pistol, but the gun is not ready to fire until a round is loaded into the chamber. Chambering a round is accomplished by pulling back on the slide and releasing it. The slide catches the top bullet in the magazine as it moves forward and guides it into the chamber, then locks into place.

Operator—Generally refers to Special Operations Personnel, however for the purposes of this article, refers to any character operating a weapon.

Single action pistol—A gun with a trigger that performs one action, that of releasing the hammer or striker to fire a round. In revolvers the operator must cock the hammer every time. These types of revolver are usually the old cowboy guns. In semi-automatics, the hammer is cocked when the pistol is loaded and re-cocked every time it’s fired. Single action triggers are notoriously “light,” meaning it doesn’t take much pressure to fire the gun.

Double action pistol—A gun with a trigger that can perform two actions, cocking and releasing the hammer. In revolvers, as the trigger is pulled, the hammer is drawn back while the cylinder is rotated. Once the trigger reaches its “break point” the hammer is released, firing the weapon. In semi-automatics, if the hammer is forward, the trigger draws the hammer back as with the revolver. In semi-automatics of this type the first shot will be double action, but all other shots are single action. This is because the slide re-cocks the weapon every time it’s fired. When a double action gun is in single action mode it takes less pressure on the trigger to fire the next round. Both semi-automatics and revolvers of this type can also be used in single action mode. This can be accomplished by manually drawing the hammer with the thumb, cocking the gun.

Round—Also cartridge; an unfired bullet still in it’s casing.

Topping off a magazine—This is when a weapon is loaded to full capacity. The operator loads the weapon then ejects the magazine, adds another bullet, then re-inserts the magazine into the weapon. Example: the Glock 19 has a 15-round magazine. If I load the magazine to 15, then insert the magazine and chamber a round, I have 14 in the magazine and one in the chamber. I can then eject the magazine and plus it back up to 15 and re-insert it into the pistol. This gives me 15 in the mag, plus one in the gun. Many operators do this. Bullets are easy to get when you don’t need them.

*****

Master Sergeant John “Chris” Grall (Ret) is a 26 year veteran of the U.S. Army. He has served 22 of those years in the Army Special Forces (Green Berets). Chris has been deployed to Afghanistan, Iraq, the Caribbean, South and Central America. He served concurrently as a full time law enforcement instructor specializing in firearms and tactics. Chris will be presenting Firearms 101, Avoiding Pistol Errors at CraftFest, Wednesday, July 9th. He also has a website: TactiQuill.com, full of free advice to authors.

Master Sergeant John “Chris” Grall (Ret) is a 26 year veteran of the U.S. Army. He has served 22 of those years in the Army Special Forces (Green Berets). Chris has been deployed to Afghanistan, Iraq, the Caribbean, South and Central America. He served concurrently as a full time law enforcement instructor specializing in firearms and tactics. Chris will be presenting Firearms 101, Avoiding Pistol Errors at CraftFest, Wednesday, July 9th. He also has a website: TactiQuill.com, full of free advice to authors.

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025

- Don’t Look Down by Matthew Becker - February 15, 2025

- The Wolf Tree by Laura McCluskey - February 14, 2025