Trend Alert: What’s Next for the Detective Novel?

By Dawn Ius

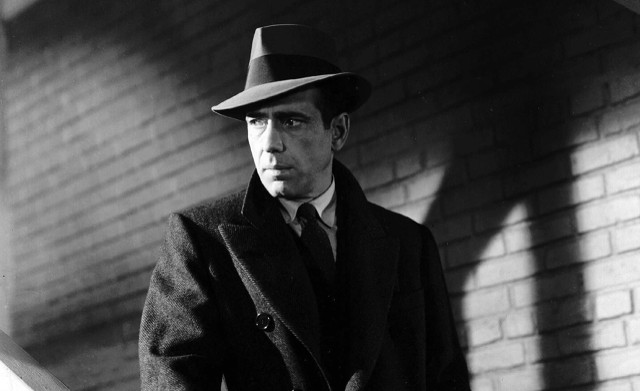

The office of a private investigator conjures up images of a dark, gritty room, the scent of whiskey and cigar smoke permeating the thick files of secrets. Stories of cheating husbands and corrupt cops.

These hired guns of old emerged in the wake of the Western hero, transforming into the iconic—and staple—character they represent in today’s crime fiction. But modern PIs have not only shrugged off their proverbial trench coats in favor of business attire, they’ve traded phone booths for smart phones and are embracing bigger, more dangerous missions that span the globe—and every possible sub-genre.

“The PI field offers endless opportunities for authors to explore every literary niche,” says Eric Campbell, publisher at Down & Out Books. “Hard-boiled, soft-boiled, cozy, thriller, high-tech, big city, rural community, and so on. PIs can investigate any kind of case while detectives (cops) are typically restricted to cases where the law was broken. This allows writers of PI characters greater flexibility in developing their stories and bending the law in ways not quite legal.”

That certainly explains why many authors gravitate to this lone-wolf hero, but what is it about the private-investigator character that makes him so endearing to readers? Sure, there are rogue cops, but most law-enforcement characters are true to their profession. So, is it the investigator’s ability to color outside the lines of the law that has given them such impressive staying power? The release this month of a remake of Murder on the Orient Express, starring Agatha Christie’s Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, emphasizes the hold such crime detectors have over readers.

“I once had a discussion with James Lee Burke about Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur from 1470, his model really for Robicheaux, and the idea of a paladin or a knight to honor a quest, right a wrong, be loyal,” says Barbara Peters, Poisoned Press publisher and the owner of the famed Poisoned Pen bookstore in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“This translates to the heroes of the American West—one on TV was actually called Paladin. I think you can see it today in our tumultuous, uncertain times with the Marvel action heroes dominating the movies, etc., including Wonder Woman and other female paladins. It’s a very long literary tradition and one particularly appealing to Americans.”

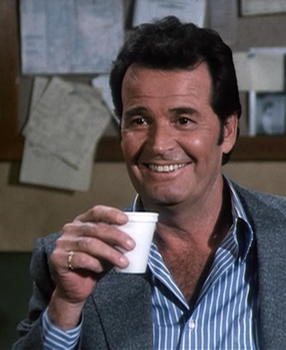

In the 1960s and 1970s, the private detectives on the page and on the screen, from Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer to The Rockford Files, Mannix, Barnaby Jones, and Cannon, were bringing order to a time of chaos. Now, as political tumult rages, could the private eye return to guide us to sanity? Certainly the new series featuring private detectives have devoted fans, with authors like Robert Crais and Reed Farrel Coleman winning awards and gaining notice.

Barry Lancet, author of the bestselling Jim Brodie series of books set in Japan, says he is drawn to writing and reading about PI characters with a strong moral code and new way of seeing the world around them.

“Their way of dealing with it could be universal, like Parker’s Spenser, or more idiosyncratic, like TV’s Monk,” he says. “Sometimes the code dominates their behavior, sometimes their way of handling the world does. I find their take on life worth knowing.”

A life that has become more complex since the time of Poe and Doyle, or Hammett and Chandler, Lancet says. “The bad guys have a lot more tools at their disposal. Not just muscle or political or corporate power, but vast pools of knowledge, expertise, and technology. Each of these can be turned against the hero, so PIs need to be versatile and quick on their feet as never before.”

For Lancet’s protagonist, that means stepping outside his American mindset when needed. In Lancet’s newest book, THE SPY ACROSS THE TABLE, Brodie is pushed beyond his comfort zone as he wrestles with murder and a kidnapping that takes him to Japan, both Koreas, and the darkest reaches of China.

For Lancet’s protagonist, that means stepping outside his American mindset when needed. In Lancet’s newest book, THE SPY ACROSS THE TABLE, Brodie is pushed beyond his comfort zone as he wrestles with murder and a kidnapping that takes him to Japan, both Koreas, and the darkest reaches of China.

In creating this globe-trotting PI, Lancet has carved out his niche in a market that is becoming more saturated, though admittedly in a subtle, almost under the radar kind of way. The PI trope has evolved so much that the character doesn’t define the genre so much as the plot.

“The best of these books start out with a simple case that over the course of the early chapters becomes increasingly complicated—and more interesting!” Campbell says. “PIs specializing in a specific area tend to be more believable. If a PI took every case that crosses his/her desk, they would not have credibility. Series have been built around PIs investigating missing children, internet crimes, financial fraud, and the like.”

That doesn’t mean character doesn’t matter. It does—perhaps even more so for the modern PI, who must compete with hundreds of new (and classic) fictional counterparts for a place in the market.

“I think the genre has, generally speaking, attracted better writers in terms of style and the variety of topics tackled,” says Charles Saltzberg, author of the Henry Swann detective series. “The classic mystery formula—dead body plus suspects plus detection equals solution—has branched out into a more complex, idiosyncratic look at the world. It’s also allowed for more complex characters, not all good, not all bad, but in the end, very human.”

And that is the appeal for Saltzberg—the ability to create a hero such as the protagonist in his Swann series—that is trying to make sense of his own personal chaos while also trying to make sense of the world.

“I don’t write classic murder mysteries,” says Salzberg, whose most recent novel in the series is SWANN’S WAY OUT. “Instead, I deal with what some might think of as lesser crimes—albeit crimes all of us are very familiar with. Fraud. Robbery. Betrayal. Identity. Even crimes of the heart. As a writer, I love ‘toying’ with the reader, doing the unexpected. In Devil in the Hole, based on a true crime, the reader knows almost immediately who the killer is, but what the reader doesn’t know, and what I’m trying to find out for myself, is why the crime was committed, and what effect the crime had on the people touched by it, including the killer himself.”

These crimes—written with the kinds of twists for which Saltzberg is known—will continue to do well in the marketplace, but as we look to the future of the genre, Peters says she’s also seeing a trend toward new authors adapting classic characters like Spenser. Or, bringing in ex-military into civilian roles as investigators—a la Lee Child’s Jack Reacher, perhaps one of the most iconic lone wolf heroes of our time.

Peters sees professional PIs like Roland Ford and T. Jeff Parker making way for characters who “fall into the role” like Petrie’s Peter Ash. “The variations are endless, but in the end, all of them are like Malory’s knights,” she says.

Peters would love to see a trend towards tough, unconventional women with the same skill set as guys, such as the well-known PIs in novels by Sue Grafton, Sara Paretsky, and Marcia Muller. On the surface it may seem like there are fewer female PIs, but Peters says she has noticed a rise in female paladins just in 2017—Kathy Reich’s Two Nights introduced a character that wasn’t Temperance Brennan, Meg Gardiner’s Unsub brought readers a fresh, determined woman loner, and The Last Place You Look by Kristen Lepionka is garnering industry buzz.

Peters would love to see a trend towards tough, unconventional women with the same skill set as guys, such as the well-known PIs in novels by Sue Grafton, Sara Paretsky, and Marcia Muller. On the surface it may seem like there are fewer female PIs, but Peters says she has noticed a rise in female paladins just in 2017—Kathy Reich’s Two Nights introduced a character that wasn’t Temperance Brennan, Meg Gardiner’s Unsub brought readers a fresh, determined woman loner, and The Last Place You Look by Kristen Lepionka is garnering industry buzz.

Though men have been the archetypal private investigators, fictional woman private investigators have existed way before even Sherlock Holmes was introduced in 1887. An author of British origin, Andrew Forrester Jr. introduced Mrs. Gladden, the first female detective character, in 1864.

“If you take a step back and include female detectives who are cops, or, say, FBI or CIA agents, the number of female PIs seems quite larger than many people think,” Lancet says.

Regardless of gender, today’s PI must have top notch skills (or a sidekick with them) instead of the muscle backup of yore, Peters says. “Patrick Kenzie had Bubba; Elvis Cole had Joe Pike…. It’s a choice authors have to make, what skill sets to endow their characters with in the PI novel, and what landscapes they work.”

But at its heart? The fundamental tenant of any novel worth its salt, of course.

“A good book is just that,” says Campbell. “One that draws you in in the first 30 pages and keeps your attention until the ‘aha’ moment towards the end when the PI figures it out all out—and you should have figured it out yourself but didn’t—and makes the connections that close the case.”

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024