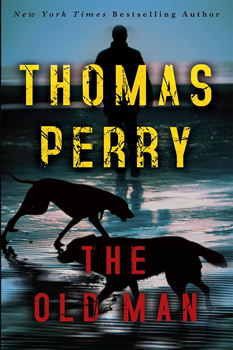

The Old Man by Thomas Perry

Unexpected Adversaries

Dan Chase, the protagonist in Thomas Perry’s riveting new novel, THE OLD MAN, lives a quiet life in Vermont. He’s a 60-year-old retiree who takes great pleasure in walking his two loyal mutts. He’s a devoted father and grandfather who keeps in touch with his daughter by phone. Though he desperately misses his late wife, he’s generally content. Then a car appears on his tranquil street and everything changes. The driver has come to kill him for an incident that occurred 35 years earlier. To survive, Dan Chase must reawaken his survival instincts and fight a private war against younger, better-equipped, and decidedly lethal adversaries. Dan’s story takes us on a tense, often chilling ride across the United States and all the way to hostile regions of Libya.

The most compelling thrillers effectively explore how old missteps and a violent past can shatter the life of an apparently ordinary person, and THE OLD MAN certainly accomplishes that, at the same time keeping the reader turning the pages. Perry has kindly agreed to share his thoughts on THE OLD MAN, his writing process, and his future projects.

THE OLD MAN tells the story of Dan Chase, a retired 60-year-old widower who lives in Vermont and who enjoys walking his two large dogs. Yet, Dan isn’t exactly who he seems. What motivates Dan?

As a young military intelligence operator 35 years ago Chase made an ill-considered decision motivated by a misplaced but noble sense of duty. After delivering U.S. aid money to a middleman, he learned the middleman kept the money instead of delivering it to Libyan rebels. He retrieved most of the money and brought it home to the U.S., but his superiors tried to arrest him and blame him for the deaths of the rebels who went unsupplied. Enraged, he held onto the money and disappeared. Thirty-five years later, he has been married and widowed, raised a daughter who’s become a doctor, and lived a good life. But now, someone has come for him—not to arrest him, but to kill him. His motivation now is simply to stay alive

You’ve set your novel in Vermont, the Chicago area, the mountains above Los Angeles, Toronto, Canada, and Libya, among other locations. How did you go about creating such vivid settings?

The settings are places a man like Chase guesses he can fit in and not be easily found. His best bet is to use the false identities he’s prepared and seem as unremarkable as he can. I live in Los Angeles and I’ve spent time in places like Chicago, Vermont, and Toronto. Libya is only researched and imagined.

Dan is 60 years old, and yet he’s able to defend himself against multiple assailants, most or all of whom are young enough to be his children. You’ve done a masterful job in making these scenes realistic. What were the challenges in portraying a mature man in combat against younger attackers?

Chase is past his prime, but he’s a trained combat and special ops veteran who has spent the years since then aware that he could be attacked at any time and need to fight. He’s remained unusually fit. When a younger man sees him, the assumption is “Old man, no problem.” But Chase is ready, strikes first, and does what he can to his opponent, not just what he hopes will be sufficient.

In the course of the novel, Dan commits a number of violent acts and manipulates other’s emotions. At the same time, he has great love and loyalty to those dear to him. How were you able to combine those conflicting characteristics in your protagonist?

I think that these contrasting qualities are present in most people, and more pronounced in some. A couple of weeks ago at the Las Vegas Book Festival I attended a talk by a Congressional Medal of Honor winner who had carried out a hopeless plan to break a siege of his outpost in Afghanistan before it could be overrun. For the hours before relief arrived he was violence incarnate, but he spoke of his comrades and his wife and kids with a love that was moving to the audience. I tried to put a little bit of that in Chase.

Chase operates on the most basic law of the planet—if someone is trying to kill you, there are no rules. He also knows that often the best way to protect himself against overwhelming odds is to manipulate others instead of dealing honestly with them. He does this to Zoe McDonald. By subletting a couple of rooms in her big apartment for cash he can buy a couple of months of invisibility, because only her name is on the lease, the utility bills, etc. When she begins to fall for him, he sees this as a new way of strengthening his hold on her and prolonging his period of safety.

Putting aside Dan Chase, who is your favorite character in THE OLD MAN, and why?

I suppose I have two favorites. I like James Harriman (also an alias), the young African American special ops contractor sent after Chase. He’s a lot like Chase probably was in his twenties. They’re patriots, they’re both trained by the same organization to further U.S. interests abroad, and they’ve needed to do violent things for that cause. They both have learned from experience that the system doesn’t really care for them. Their shared loyalty to the country is paired with a sense of justice, and forces them to behave in similar ways. I also like Zoe, the woman Chase exploits to stay alive. I find her situation as a middle-aged woman whose life has toppled around her—failed marriage, one child who is a disappointing jerk and one who’s probably always going to be far away, a bit too old to pursue her musical career now—to be interesting, and I like her response to the challenges.

You’ve written and produced television shows. What are the differences in writing a TV script and a novel? And does your entertainment-industry background help you write novels?

Any writing experience is good, which is probably why so many reporters, lawyers, and advertising people are writing good books. Writing for TV is a good way to learn lots of things. You learn to work with the inflexible discipline imposed by the calendar. When a script is due it’s got to be ready. There is also a value to being one of a group of professional writers who try to be both critical and helpful. Being forced to think hard about how to keep an audience’s attention is good too. It helps a writer to think about issues like pacing, how long a single speech can be, and how long a scene can be. Hearing dialogue spoken rather than read exposes flaws—pompous wording, false notes, clichés. The only negatives I can think of are that television writing can be grueling, and the writer is doing a work for payment, not pursuing a free and unlimited play of the imagination.

You’ve written both series and standalone novels. What do you find gratifying about each approach? Are there downsides to either, and if so, what?

When I started writing, I always told myself I’d never write a series. I wanted to write the best novels I could, and very few great novels were anything but standalone books. That went fine until I finished Vanishing Act, about Jane Whitefield, a half-Seneca woman who takes in people who have reason to believe they’re about to be murdered and makes them disappear. I’d finished the book, but I knew much more about the character that I still wanted to say, so I started a sequel, and the series was launched. I also found that from time to time I get curious about the protagonist of The Butcher’s Boy, my first novel, so after 10 years I wrote a sequel, and after 30, I got curious about him again. A series allows a writer to exercise these urges to revisit a character. But standalone books give him a chance to free his imagination to find and invent new ones.

Who are some of your favorite writers? Can you include one or two NON-thriller/mystery writers among them?

I was an English major and then went to graduate school for my Ph.D., so I spent a lot of my early years reading. My real favorites are still the books of Joseph Conrad, William Faulkner, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, E.M. Forster, and so on. As for mystery and thriller writers, I would rather not simply add to the applause for fine established writers, even though some are friends. I try to read as many new authors as I can each year, and I’d like to mention a few of this year’s stand-outs: Every Man a Menace by Patrick Hoffman, The Coaster by Erich Wurster, The Prometheus Man by Scott Reardon.

In THE OLD MAN, you write about, among other things, the workings of firearms, the NSA’s method of locating fugitives, the Libyan tribal structure, and the ways in which a person can hide his or her identity. Could you describe how you do your research?

I’ve often said that research is what you do when you don’t feel like writing, but want to preserve the illusion of progress. Most of my research is of two kinds: reading, listening, observing, and collecting interesting ideas in an undirected way, or going after a particular piece of information I need until I find what I can know about it. I also subscribe to a number of magazines with different subjects and points of view, including one gun magazine, which keeps me informed of what’s new in firearms.

Writing conferences are rife with advice for aspiring writers. What advice would you give to authors who’ve published several novels but who haven’t yet broken out?

The first thing I’d like to suggest to them is that maybe “breaking out” isn’t the best goal for a career. It’s something that might happen to a writer rather than something he can do. There are a few writers whose names we all know and see on every bestseller list the day their books are published. Some of them are very good writers, and some are very bad writers. Few of us will ever be one of those names, no matter what we do. The most accessible goal is to learn to be a better writer. We can all do that. It will always be good for us, and it may even make us more likely to be noticed.

Would you describe your writing process? Outlining or not, places you write, hours per day?

My writing process has evolved with changes in my life. When our kids were young, I used to drive them to school and come home to work until my wife picked them up from school at the end of the day. I would try to be available to them whenever they were home, which probably convinced them that I never did any actual work. Now my wife and I sit at two desks 10 feet apart and write from the time we return from taking our dogs to the park for a run until we need to stop to take them out in the late afternoon. I write in longhand on plain typing paper until I have a big chunk of story, and then type the second draft into a laptop. I never outline unless I’m wondering if I might be lost.

Please tell us about your next project.

My next book features a man who makes and plants bombs.

*****

Thomas Perry is the bestselling author of over twenty novels, including the Edgar Award winner The Butcher’s, a String of Beads, Poison Flower, and Forty Thieves. His Metzger’s Dog was voted one of the best 100 thrillers ever by NPR listeners.

Thomas Perry is the bestselling author of over twenty novels, including the Edgar Award winner The Butcher’s, a String of Beads, Poison Flower, and Forty Thieves. His Metzger’s Dog was voted one of the best 100 thrillers ever by NPR listeners.

To learn more about Thomas Perry, please visit his website.

- Jeffrey Archer - October 12, 2023

- David Bell - July 7, 2023

- Up Close: Daco Auffenorde - October 31, 2020