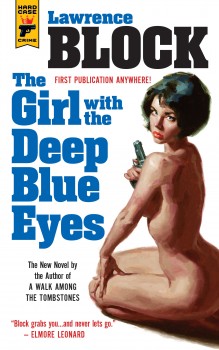

The Girl With The Deep Blue Eyes by Lawrence Block

A Master of Crime Fiction Tells All

There are few contemporary authors I respect as much as Lawrence Block, and I’m not the only one who feels that way, as his list of honors indicates: Grand Master Award from Mystery Writers of America, four Edgars and four Shamuses, Lifetime Achievement Award from the Private Eye Writers of America, Diamond Dagger for Lifetime Achievement Award from the Crime Writers Association . . . and I’m just getting started.

The length of Larry’s career is equally impressive—more than five decades. Read that again. More than five decades. Longevity isn’t as important as quality, though, and he just keeps getting better, never disappointing in the four (count them, four) splendid series that demonstrate the depth of his talent, featuring cop-turned-detective Matthew Scudder, globetrotting insomniac Evan Tanner, introspective assassin Keller, and hilarious bookselling burglar Bernie Rhodenbarr (my personal favorite).

Among Larry’s more than 100 books, there are two non-fiction volumes that ITW members should consider required reading: his collection of essays about his friendships with such crime-writing legends as Donald E. Westlake and Evan Hunter/Ed McBain (The Crime of Our Lives) and his writing book (Write for Your Life).

But it’s Larry’s latest, THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES, that we’re here to talk about—an amazing update on the scorchers that James M. Cain pioneered with The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity..

Hard Case Crime published THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES, giving it one of their fabulous covers that re-create the classic look of crime novels in the 1950s and 1960s. The cover is hot, but your novel is even hotter. What inspired you to take a new look at this powerful sex-and-murder subgenre?

Hard Case reissued an early pseudonymous book of mine, Borderline, and damned if it didn’t get far better reviews than I felt it deserved. And I was telling my wife that it might be fun to write something similar—fast-paced, pulpy, with the narrative drive more important than the plot. “It might,” she said, and 15 seconds later—no joke—I sat up and said, “I’ve got an idea.” Now most ideas wither on the vine, and that’s probably just as well, but this one stayed with me and grew, and less than two months later I was writing it.

Borderline was published in the 1950s when you were learning your craft, writing pulps under your many pseudonyms (ten that I know of). Damned good pulps. Invaluable training. Booklist described the reissue of Borderline as a gleeful mix of “soft-core pornography with a thriller plot.” THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES fits that description also, except that its sex scenes are more than soft-core. What made you decide to push the “borderline,” so to speak?

Changing times, I suppose. Back in the old Nightstand/Midwood days, which we’re now calling Midcentury Erotica, the sex scenes were as graphic as they were allowed to be, and were specifically intended to arouse the reader once a chapter. Well, the world has changed, and censorship has disappeared, so it was natural for me to make the book as candid as possible—and at the same time I was no longer aiming for an erotic effect per se, just trying to write frankly and honestly. I’d gone there before—in my post 9/11 novel, Small Town, in 2003, and more recently in Getting Off. (I received a surprising amount of flak over Small Town from readers who were used to the more circumspect Bernie Rhodenbarr; they felt they’d been ambushed. Happily, the cover of Getting Off let everybody know what to expect.) I’m interested in people’s sex lives, and I have to assume readers are, too. Faubion Bowers observed that sex is the one interesting thing even boring people do. I’d hope my characters aren’t boring, but in any event their sex lives are interesting.

In some examples of this sex-and-murder subgenre, the reader is only told that the sex is powerful whereas you show it vividly and make the killer’s motivation convincing. The set pieces are amazing narrative accomplishments. Over the years, I wrote very few sex scenes because I always felt I was censoring myself. How do you manage to avoid the trap of self-censorship? Was there ever a moment when you thought you’d gone too far?

No, never. For some reason it all rang true for me, and I just let it happen. You know, I grew up reading John O’Hara, and he did more in sex scenes with pure dialogue than most people could manage with an entire film crew. And, while I wrote THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES entirely on spec, I figured Charles Ardai at Hard Case was the most likely publisher for it. And I knew I didn’t have to worry about holding back as far as Charles was concerned. He’d proved that with Getting Off, where he actually suggested a wicked addition to one scene that put it way way over the top. (And I , who ordinarily welcome suggestions as enthusiastically as Trump welcomes immigrants, promptly embraced it wholeheartedly.)

Lest we give readers the impression that this is erotica and not a thriller, I need to emphasize the game of wits that the killer plays with the police and the rocket pace of the story, with shockers I could never have predicted. The leanness of the prose is a master class in thriller writing. One technique I particularly admired is a scene that you describe twice, making me (and the police) believe the first version, then revealing what actually happened. Did you ever have a sense that you were finding new ways to tell this kind of story?

I know the scene you’re referring to, and it seems to me I knew almost from the moment I had the idea for the book that I would structure it that way. By the time I sat down to begin the book, I’d had the scene in mind long enough to know how to write it. And yet other things weren’t planned at all. The realtor, who’s surely a significant presence in the very first chapter, just turned up out of nowhere. She shows him a house, his offer’s accepted, and he asks how they should celebrate. And she takes off her wedding ring and drops it in her purse. Now where the hell did that come from? And where did she come from? Writing’s a mystery, isn’t it? The more I do it, the less I understand the whole business.

One final question and a change of topic. Recently one of your Matthew Scudder novels, A Walk among the Tombstones, was released as a feature film, starring Liam Neeson. I liked the movie a lot. What was your own reaction?

The film was ten years in development. After all that time, I didn’t know what to expect, but I’m happy to say I loved it, thought Liam Neeson was the perfect choice, and can’t say enough about the job Scott Frank did as writer and director. The color/noir depiction of New York City is stunning. Meanwhile, a television producer has optioned The Girl With the Deep Blue Eyes and is shopping it for a one-season series, probably on cable. Dunno if anything will happen, but I’m hopeful. And no, I have no idea who they might cast; aside from the female lead’s eye color, I’d say it’s wide open.

I speak for a lot of people when I say that my fingers are crossed. Thanks for visiting The Big Thrill. This was a fun conversation.

*****

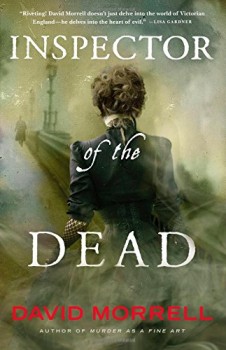

David Morrell is the author of First Blood, the award-winning novel in which Rambo was created. He has a Ph.D. in literature from Penn State and was a professor in the English department at the University of Iowa. His numerous New York Times bestsellers include the classic spy novel The Brotherhood of the Rose, the basis for the only television mini-series to be broadcast after a Super Bowl. An Edgar and Anthony finalist, a Nero and Macavity winner, Morrell is a recipient of three Bram Stoker awards and the Thriller Master award from ITW. His latest novels are the Victorian mystery/thrillers, Murder as a Fine Art and Inspector of the Dead.

David Morrell is the author of First Blood, the award-winning novel in which Rambo was created. He has a Ph.D. in literature from Penn State and was a professor in the English department at the University of Iowa. His numerous New York Times bestsellers include the classic spy novel The Brotherhood of the Rose, the basis for the only television mini-series to be broadcast after a Super Bowl. An Edgar and Anthony finalist, a Nero and Macavity winner, Morrell is a recipient of three Bram Stoker awards and the Thriller Master award from ITW. His latest novels are the Victorian mystery/thrillers, Murder as a Fine Art and Inspector of the Dead.

To learn more about David, please visit his website.

- AudioFile Spotlight: March Mystery and Suspense Audiobooks - March 17, 2025

- Africa Scene: Shadow City by Natalie Conyer - March 17, 2025

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025