From my observations, people, especially the young, are surprisingly ignorant of history. When I taught writing courses to college students, I was dumbfounded by how little they know about historical events.

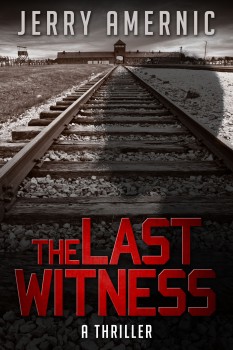

That got me thinking about some important periods in history, and what a travesty it would be if they were forgotten, only to suffer the risk of history, as they say, repeating itself. Thus became THE LAST WITNESS, a novel about the last living survivor of the Holocaust. In the book, the character’s one hundredth birthday takes place in 2039, but the world has all but forgotten.

Like many novels, it was first turned down by various publishers, one of whom said he had to “suspend disbelief” with the premise that people would know so little about the Holocaust a mere one generation down the road.

Really?

To prove my point, I decided to make a video—but not your regular, book-promo thing. I had a mission. A videographer and I spent an afternoon asking university students in Toronto, where I live, what they know about the Holocaust. And since this was a few days before November 11th, we also asked them about World War II.

What did we find? Many students didn’t know what happened at the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, who FDR and Churchill were, or what the Holocaust was all about. “I’ve heard of the Holocaust but I can’t explain it,” one student said. When I asked how many Jews were killed, another said, “thousands”—which is a far cry from six million.

Not a single student knew what The Final Solution was, or had heard of Joseph Mengele, and most had no idea who the Allies were, and yet, our video was shot just before November 11th—Remembrance Day in Canada, Veterans Day in the United States. It made me wonder: What would a veteran who stormed the beaches of Normandy with Allied forces on June 6th, 1944 think knowing that university kids today know nothing about what happened that day?

I don’t blame the kids. They are The Lost Generation when it comes to history, victims of a school system that no longer teaches it. This is a big problem in Canada, the U.S., Great Britain, and other countries. As a result, I don’t think it’s such a stretch to create a world in 2039 where rampant ignorance abounds about seminal events.

My research for THE LAST WITNESS began long before we shot that video. Several chapters in the novel contain flashbacks with my protagonist, a hidden child in the Jewish ghetto of his birth, and later, as a little boy at the death camp —Auschwitz— where all his family is lost. He is the only one who survives. But there was little point writing a historical thriller about a subject like this without meeting real-life, child survivors. So I did.

My research for THE LAST WITNESS began long before we shot that video. Several chapters in the novel contain flashbacks with my protagonist, a hidden child in the Jewish ghetto of his birth, and later, as a little boy at the death camp —Auschwitz— where all his family is lost. He is the only one who survives. But there was little point writing a historical thriller about a subject like this without meeting real-life, child survivors. So I did.

Gershon Willinger was three years old when liberated by U.S. soldiers from a concentration camp in 1945. Like the character in my novel, he was the only one in his family who made it out. He doesn’t remember much, but for his entire life he’s felt claustrophobic in tight closed spaces, and he harbors a fear that those closest to him—even his wife—will leave him. Today, he’s a grandfather who lives just north of Toronto.

Did Gershon think my premise about the world not knowing much about the Holocaust in 2039 was far-fetched? No. In fact, not one survivor I met thought so. Miriam Ziegler was nine when liberated by the Red Army at Auschwitz. There is a photo of children standing behind a barbed-wire fence on the day they were freed, and Miriam is in it. She doesn’t like to talk about her experiences, but they’re seared into her memory, including that of the infamous Joseph Mengele, the Nazi doctor who performed twisted tests on children, especially twins. Miriam remembers seeing him walking around all the time. “The man in charge,” she said.

Some former child survivors readily go into schools to speak about their experiences. One of them, Elly Gotz, spent three years as a teenager in the Jewish ghetto in Vilnius, Lithuania. When he and his parents had given up hope and were about to commit suicide, they were freed, and all three survived. Today, Elly is a robust eighty-five-year-old who lectures at schools and for other groups. He even helped prepare videotaped testimonies of 450 Holocaust survivors, and has been honored for his work by the Government of Ontario. Elly was invaluable to me when I asked him to fact-check my historical flashbacks about life in the ghetto.

As a writer who is a stickler for accuracy—that goes for historical novels, too—I don’t like to bend history. My initial plan was to write about the Warsaw ghetto, the biggest Jewish ghetto of all, and follow my character as he got caught up in the Warsaw ghetto uprising, a signature event in World War II where Jews rose up to fight their Nazi oppressors. But when I discovered no Jews from Warsaw went to Auschwitz, I abandoned that idea.

The next biggest ghetto was in Lodz, Poland. Thousands of Jews were moved from there to Auschwitz, so I read everything I could find about the Lodz ghetto. I learned how children sneaked over the wall that divided the Aryan side from the Jewish ghetto to steal food for their family, how countless Jews lived in sewers below the city to stave off capture, and how they were transported like cattle—worse than cattle—in cold vile trains to the death camp.

All this became part of THE LAST WITNESS, but the book didn’t start out as a thriller. It was meant to be a commentary on how society is becoming historically illiterate, but I also wanted it to be a novel that would make you read from one page to the next.

In the story, my 100-year-old character becomes crucial to a missing-person investigation when his great-granddaughter, a schoolteacher, suddenly disappears. Thus, there are two story lines— the modern or near-future story, and the flashbacks about his life as a little boy trying to survive in what can only be described as hell.

Still, the book was missing something—pacing, or as writers like to say, it needed legs. I rectified that by making the NYPD detective involved in the missing-person investigation a much stronger character than he was in earlier drafts. Not only does he become the face of the larger society that has much to learn about what happened to European Jews in the 1940s, but he is larger than life at 6’5” and 330 pounds. I also threw in some neo-Nazis who make things interesting, and tightened the book up with a few final edits.

At the end of the day, the job of a thriller writer is to make the story believable and credible for the readers, and to keep those readers on the edge of their seats. Writers do this in different ways, but for me, weaving back and forth between the past and present (or in this case, the near future) is one way to tell a tale. I definitely learned a lot in this project, especially through those former child survivors, and hopefully my reader will too.

For more information, go to THE LAST WITNESS. The book is available on Amazon. You can see Jerry Amernic’s video with the university students here.

*****

Jerry Amernic is a writer who lives in Toronto. He has been a newspaper reporter and correspondent, newspaper columnist, feature writer for magazines, teacher of journalism, and media consultant. His most recent novel is The Last Witness, which is about the last living survivor of the Holocaust in the year 2039. Soon to be released is his biblical-historical thriller QUMRAN. Jerry’s first novel, Gift of the Bambino, was published in 2004 and will soon be re-released as an e-book.

Jerry Amernic is a writer who lives in Toronto. He has been a newspaper reporter and correspondent, newspaper columnist, feature writer for magazines, teacher of journalism, and media consultant. His most recent novel is The Last Witness, which is about the last living survivor of the Holocaust in the year 2039. Soon to be released is his biblical-historical thriller QUMRAN. Jerry’s first novel, Gift of the Bambino, was published in 2004 and will soon be re-released as an e-book.

To learn more about Jerry, please visit his website and follow him on Facebook.