Imagine you’re forty years old. You’re married with a teenage daughter. You’ve been at your job for eighteen years. And one day, you come home to a message on your voicemail: you’ve been fired (“downsized”) and shouldn’t come back in to work.

For many, this would be the first step down a path of defeat, desperation, and despair. They’d find themselves in a dark room curled up in a ball — or in a dark bar curled up in a bottle.

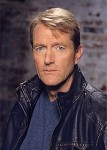

But not Lee Child.

In the mid-1990s, he received that call — the third message on his voicemail after returning from vacation. Child’s career as a British television director was over. His response? He went to the store, “bought six dollars’ worth of paper and pencils,” and sat down to write his first novel, KILLING FLOOR. It was about a man who had been downsized from the U.S. military, who wanders the American landscape righting wrongs and dispensing justice. His name was Jack Reacher.

Today, nearly two decades later, Child is one of the most successful writers in the United States, if not the world, selling more than 50 million books. And Reacher, well, he’s one of the most celebrated characters in fiction. The millions of Reacher fans (“Reacher creatures”) soon will see the beloved character immortalized in ONE SHOT, a film starring Tom Cruise as Reacher. Paramount Pictures is so confident in the film that it recently moved up the release date.

Today, nearly two decades later, Child is one of the most successful writers in the United States, if not the world, selling more than 50 million books. And Reacher, well, he’s one of the most celebrated characters in fiction. The millions of Reacher fans (“Reacher creatures”) soon will see the beloved character immortalized in ONE SHOT, a film starring Tom Cruise as Reacher. Paramount Pictures is so confident in the film that it recently moved up the release date.

On March 18th I met with Child in a “mentor forum” hosted by the International Thriller Writers Debut Authors Program, where he dispensed his wit and wisdom to a small group of the newest generation of thriller writers seeking to learn from a master. Participating via Skype, writers from across the country spent over two hours peppering Child with questions about writing, book promotion, and the publishing industry. To his credit, Child agreed to answer “any question at all.” And he did so, breaking only to fill up his mug with coffee and to give an occasional longing glance at his computer where he is putting the final touches on his forthcoming Reacher book, A WANTED MAN.

Reflecting on the time with Child, it struck me that his advice wasn’t just about being a successful writer. It was about being a successful person in whatever your job or endeavor. Given the current economic climate, I wanted to share some of his insights that I think transcend the writing world.

“Eighty percent of success is showing up.” Okay, that’s Woody Allen, not Lee Child, but in responding to a question by a debut author about how to conduct effective book signings, Child quoted Allen. Child said, “Never forget this is a long game. Penetrating the culture is slow and takes years and years and years. It literally is true that it takes 10 years to become an overnight success. If you show up to a signing and there’s 3 people, don’t worry about it; tomorrow may be only 2 people. Next year, there will be more. Five years there will be still more. And 10 years, they will be screaming and clapping as you walk in the room, so never get discouraged.”

The “long game” and tenacity were recurring themes for Child during the forum. He said that’s how he survived the early days of his writing career: “I did this for years — today everyone assumes ‘Lee Child #1 bestselling author,’ but I was completely unknown. I’d be on tour alone in a hotel room, I’d go through airport after airport and my books were not on the shelves, and I was basically invisible. I used to think I was published by the witness protection program.” But he stuck to it “a book a year” and it paid off. A lesson in life, more than writing.

Know when to break “the rules.” Many writers in the forum asked Child about what “rules” in writing he follows when drafting his novels. Child said he follows few hard-and-fast rules. And he’s wary of the cottage industry of how-to books on novel writing. “These books usually are completely wrong in my experience and fatal in my judgment.” For instance, Child scoffed at the conventional rule that writers must “show, don’t tell.” He said writers are called “storytellers, after all, not story showers.” Because of the show-don’t-tell rule, Child thinks that many writers are so scared of “telling” that they manipulate their work, such as having characters peer in a mirror and describe themselves, rating their own looks. “Who does that in real life?” Child laughed. “There’s nothing wrong with just writing ‘he was a tall man with brown hair.’ Just tell the damn story.”

Know when to break “the rules.” Many writers in the forum asked Child about what “rules” in writing he follows when drafting his novels. Child said he follows few hard-and-fast rules. And he’s wary of the cottage industry of how-to books on novel writing. “These books usually are completely wrong in my experience and fatal in my judgment.” For instance, Child scoffed at the conventional rule that writers must “show, don’t tell.” He said writers are called “storytellers, after all, not story showers.” Because of the show-don’t-tell rule, Child thinks that many writers are so scared of “telling” that they manipulate their work, such as having characters peer in a mirror and describe themselves, rating their own looks. “Who does that in real life?” Child laughed. “There’s nothing wrong with just writing ‘he was a tall man with brown hair.’ Just tell the damn story.”

The conventional rules dispensed in these types of how-to books also are fatal, Child said, because they encourage writers not to follow their instincts and own good judgment. “Writing is such an organic and personal thing, it needs its own heart beat, its own DNA — it can’t be done by committee. If Book X says you can’t do this, and Book Y says you must do this, as soon as you start thinking along those lines, you’re lost, the spark is gone, the vividness is gone because it becomes a committee decision. Write exactly what you want to write, even if the rules say it is ‘wrong.’” That’s the approach Child takes with Jack Reacher. “In all my books Reacher does disgusting things — he shoots people in the back, he cheats, he steals, and he wears filthy clothes day after day. I should do none of that, but people respond to the integrity of the character more than conventional rules.” This is not to say that Child doesn’t follow certain rules when he writes (he noted several); he just refuses to put conventional wisdom over his instincts and judgment. There’s a lesson there for everyone.

Nice guys don’t always finish last. Several of the debut writers asked Child to give his best advice on how to have a long career as a novelist in a very difficult market. Child’s advice wasn’t about plot, how to create a compelling character, or writing techniques. Surprisingly, it boiled down to being a “cheerful, pleasant person.” For publishers, he said, “if you’re a good team player, a member of ‘the family’ — never judgmental or vindictive and tolerant of mistakes — this is a giant intangible.” The worst thing a writer can do is be unapproachable or make the publishing team scared to pick up the phone. Mistakes are inevitable, he said, but when they happen “you need to take a deep breath and recognize that it is not about this book, or this launch, it is about a 5 or 10 year progression.” Though the advice was geared toward writers, I know from first-hand experience as a corporate litigator for more than 15 years that it rings true in the corporate world. It’s not just about being the best in your field; being positive, approachable, and likeable breeds loyalty.

Child approaches his readers in the same way. When asked for his advice about book signings, for instance, Child said “90 percent of the time, don’t talk about your book. The key here is to be polite, be generous with your time, try and connect . . . if they like you, everything else falls into place.” Child doesn’t just try and connect with the reader in person, but also every time he puts pen to paper because ultimately “books are just transactions between the reader and the writer.”

Child approaches his readers in the same way. When asked for his advice about book signings, for instance, Child said “90 percent of the time, don’t talk about your book. The key here is to be polite, be generous with your time, try and connect . . . if they like you, everything else falls into place.” Child doesn’t just try and connect with the reader in person, but also every time he puts pen to paper because ultimately “books are just transactions between the reader and the writer.”

Finally, Child values being a “good guy” to other authors. When a debut writer asked him about the best way to approach authors for book jacket endorsements (“blurbs” in writer jargon), Child had similar advice: be polite and friendly and if the writer can’t or won’t give a blurb, be gracious about it. He noted that he receives 80-100 requests for blurbs a week. “I love to discover new writers and I respond to as many requests as I can.” Child said that he’s tried to help so many authors he fears his blurbs have been devalued, and he joked that a British magazine once did a satire lining up all the books Child had blurbed. When asked about his favorite of all the blurbs he’s given, Child revealed (as he did throughout the day) his sense of humor. He said his favorite was for a book that is a parody of a thriller: “Of all the books I’ve read this year, this is one of them.”

Know your own limitations. Given his tremendous success, it is hard to think of Child having limitations when it comes to his work. But during the forum he readily identified areas in his writing where he claimed to need improvement. He also thought he would be terrible at adapting his books to screenplays for the big screen. “You need emotional distance, so you shouldn’t work on your own stuff.” He also couldn’t effectively employ the “brutal” editing and changes needed for a book to work well as a film. Besides, he loves to see how others interpret his work. “It’s a pretentious example,” he said, “but if I was Bob Dylan I wouldn’t want to just hear an exact interpretation of All Along the Watchtower — I’d want the Hendrix version.”

Give Back. Child had nothing objectively to gain by meeting with a dozen new writers on a Sunday afternoon. He wasn’t being paid to do it. He wasn’t getting publicity for it (he didn’t know THE BIG THRILL would ask me to write a story about the forum). All he knew was that a handful of new writers wanted his advice. He put no time limitations on the meeting and even learned how to use Skype to allow him to connect with people spread across the country. All he asked was that in future, when success hopefully touched us all, that we do the same to the next generation of writers.

Give Back. Child had nothing objectively to gain by meeting with a dozen new writers on a Sunday afternoon. He wasn’t being paid to do it. He wasn’t getting publicity for it (he didn’t know THE BIG THRILL would ask me to write a story about the forum). All he knew was that a handful of new writers wanted his advice. He put no time limitations on the meeting and even learned how to use Skype to allow him to connect with people spread across the country. All he asked was that in future, when success hopefully touched us all, that we do the same to the next generation of writers.

Child closed by saying that our “takeaway” should be this: “It’s a long game. It will look bad on plenty of days, but hang in there, keep showing up and see where you are in 10 years.” Given his inspirational story of turning a potential life-shattering event into a chance to reinvent himself and live a writer’s dream, that’s advice worth following — for writers and everyone else.

*****

Anthony J. Franzeis a lawyer in the Appellate and Supreme Court practice of a large Washington, D.C. law firm, and author of the debut legal thriller, THE LAST JUSTICE. In addition to his law practice, he is an adjunct professor of law, teaching courses in Federal Courts and Appellate Practice. Franze is a graduate of Notre Dame Law School and the author of numerous scholarly works. He lives in the D.C. area with his wife and three children.

Anthony J. Franzeis a lawyer in the Appellate and Supreme Court practice of a large Washington, D.C. law firm, and author of the debut legal thriller, THE LAST JUSTICE. In addition to his law practice, he is an adjunct professor of law, teaching courses in Federal Courts and Appellate Practice. Franze is a graduate of Notre Dame Law School and the author of numerous scholarly works. He lives in the D.C. area with his wife and three children.

23 Responses